Introduction

Dental fear and anxiety are both significant characteristics that contribute to neglect of dental care throughout life. There is a dependent correlation between painful stimulus and increased pain perception, resulting in a prolonged experience of pain and also exaggeration in the memory of pain.1 The estimated prevalence of dental fear and anxiety in children and adolescents ranges from 5.7% to 20.2%, affected by factors such as age, sex, cultural context, socioeconomic status, presence of dental caries, history of dental pain, and previous invasive dental treatments.2

The aetiologies of dental fear and anxiety are known to be multifactorial, being affected by endogenous as well as exogenous factors. Endogenous factors include personality traits and the individual’s cognitive ability to cope with various types of fears. Exogenous factors are mostly related to previous traumatic experiences, which might have occurred throughout childhood.3,4 Studies have also reported that patients who experienced dental fear and anxiety when visiting the dentist are those individuals who have decayed and missing teeth, and reported irregular attendance at the dental practice.4 This shows that the more positive a child’s experience when visiting the dentist, the less likely they are to become fearful whenever they face a negative experience.5

In addition, dental anxiety is known to be the major contributing factor for irregular dental attendance to avoid a dental procedure.6 Thus, patients with a history of regular dental attendance reported less anxiety than those with irregular attendance (20.9% versus 79.1%).7 For instance, a study reported that children between six and 12 years of age who were more dentally anxious had higher odds of having caries when compared with children without reported dental anxiety. Hence, dental anxiety is a significant predictor of the presence of caries and might affect oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). This effect was even more pronounced and statistically significant when associated with follow-up sessions.8

Preventive treatment for children using fluoride varnish is known to be effective in reducing the risk of future dental caries development, especially in children with high caries experience. Moreover, providing oral hygiene instructions, dietary advice reinforcement and in-office fluoride applications through regular follow-up appointments is recommended in children who attended for previous dental treatment with moderate to high caries experience.9

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate parental reports on the oral health status and degree of dental anxiety in recall children aged between five and 10 years old attending a paediatric dental service for a dental check-up appointment, and its correlation to children’s caries experience and baseline factors such as age, sex, parental educational background, and history of dental anxiety based on dental records.

Materials and methods

This questionnaire- and patient records-based study is nested in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) that was conducted in the Department of Preventive and Paediatric Dentistry at the University of Greifswald, Germany. The study sample included 70 healthy children aged between five and 10 years, who attended for a follow-up appointment after completing their dental treatment in a specialised paediatric dental clinic in a university setting (University of Greifswald) between February and July 2022. The check-up appointment involved fluoride varnish application (Profluorid; VOCO Germany) with five different tastes (mint, cherry, melon, caramel, bubble gum). The ethical approval to conduct the RCT was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the medical school from the University of Greifswald.

Inclusion criteria

Recall children who were healthy, or grade I or II according to American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical classification system,10 aged between five and 10 years old, who presented for the follow-up appointment after attending previously for dental treatment (Table 1) were included.

Exclusion criteria

Medically compromised patients who were grade III, IV, or V according to the ASA classification, or who presented to the appointment with pain and discomfort that should be treated, were excluded.11 In addition, children who presented for the first time in the dental clinic, or children who reported an allergy to fluoride varnish, were not eligible for participation. Parental consent was required for the child’s participation in the study, as shown in Figure 1.

Questionnaire and data collection

The questionnaire was in the German language and consisted of two parts. The first part collected general baseline information, e.g., sex, age, and educational background of the parents. The second part of the questionnaire involved structured questions regarding parental report of child’s dental fear and anxiety towards the dental appointment, using a dichotomously ‘yes/no’ single question.10 Parental assessment of the child’s behaviour during the study’s dental check-up appointment was assessed using five choices (very good, good, satisfactory, sufficient and inadequate) based on a Likert scale. In addition, parents were asked to assess the current oral health status of their children using five grades (very good, good, satisfactory, sufficient and inadequate) based on a Likert scale.12

Dental practitioners who performed the dental treatment in this study were either paediatric specialists (n=3) working at the Department of Preventive and Paediatric Dentistry at the University of Greifswald, or postgraduate students (n=4) undergoing a three-year master’s programme in paediatric dentistry, who were trained on the same concepts of dental behaviour management according to World Health organisation (WHO) criteria (dmft/DMFT).

General patient data regarding age, dmft/DMFT and previous history of dental anxiety were collected through reviewing the patients’ specific records (Dampsoft; Germany). History of previous dental appointments was reviewed to assess the overall degree of acceptance and co-operation of the child. The following parameters were reviewed in the dental records to assess the history of dental fear and anxiety: sitting on a parent’s lap during the treatment; crying throughout the treatment; and, refusal of the entire treatment or a specific treatment step. The caries experience was categorised as suggested by the WHO oral health survey method, which is based on dmft value acquired through clinical examination during the dental visit (Table 2).13

Patient records were collected on a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel 2013, then analysed descriptively. Means and standard deviation were also calculated with Excel 2013. Differences in clinical outcomes (dental anxiety, oral health, dental behaviour during the study’s appointment, etc.) were analysed using the chi-square test. In this study, p<0.05 was defined to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 70 healthy recall children (male: n=43; female: n=27) with a mean age of 7.1±1.87 years presenting to the Department for a normal dental check-up and receiving fluoride varnish were included in this study. The mean dmft/DMFT was 3.5/0.24 (±SD 3.50/3.50). Male children had slightly higher dmft/DMFT values, as shown in Table 3. In addition, 52.9% (n=37) of these children were previously treated under sedation (either nitrous oxide sedation or dental general anaesthesia (GA)) and had a history of dental extraction. Dental restorations (62.9%, n=44) were the most prevalent dental treatment provided for these children.

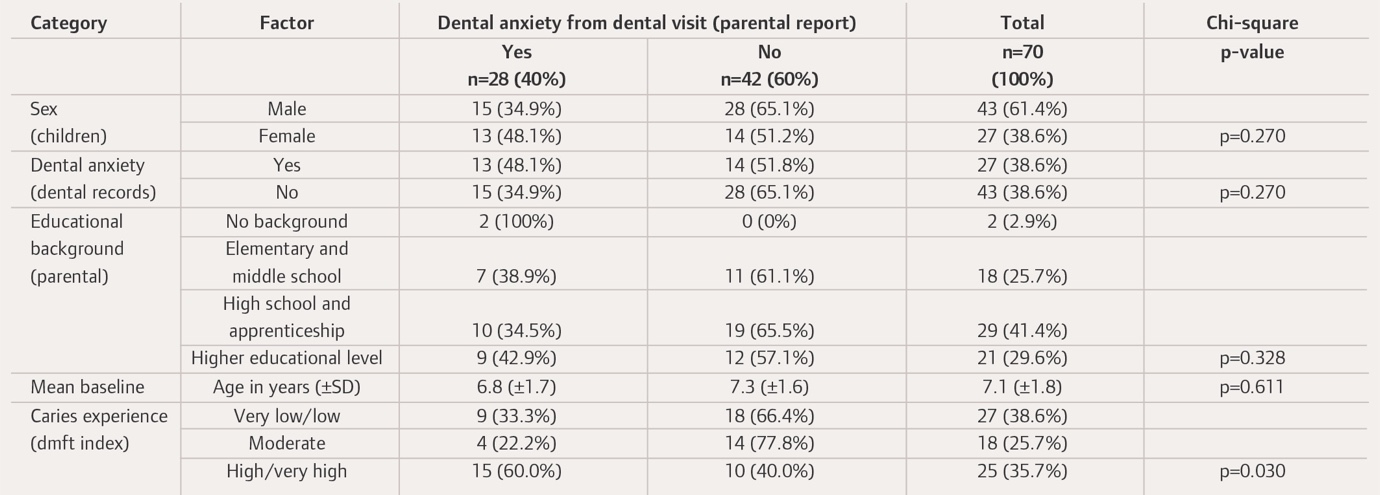

Parental assessment was based on a questionnaire response to the third question, where the parents were asked if the child is afraid of the dental visit. Assessment criteria involved answering only dichotomously with yes or no. A total of 28 parents assessed their children (male: n=15; female: n=13, with mean age of 6.8 (±1.7) years) to be dentally anxious, while non-anxious children (n=42, 60%) had a slightly higher mean age (7.3 (±1.6); Table 3). Moreover, the frequency of dental anxiety from the dental visit according to the parental report was neither statistically different for sex nor educational background and age, but was associated with caries experience (p=0.03) in the primary dentition based on dmft index (Table 3; Figure 2).

Parental responses regarding assessment of oral health status and the child’s behaviour during the dental visit were categorised to ease statistical analysis, in which “very good” and “good” were combined and classified as good oral health status. Both “satisfying” and “adequate” were combined and classified as satisfying oral health status. When parents evaluated oral health status as inadequate, this was classified as poor (Table 4; Figure 2). In addition, the oral health status of the child correlated with the degree of caries experience according to dmft index category (Table 4).

Most parents had a good feeling about the oral health status of their child, as this rating correlated with the WHO caries experience assessment (Table 2). Nevertheless, eight parents (11%) rated the oral health as good, even though they belonged to the high caries experience group (Table 4). A significant correlation was observed (p<0.05) between caries experience based on dmft index and the parental evaluation of oral health status in children (Table 4).

Parental evaluation of their child’s behaviour during the dental visit was reported in the majority of the cases (n=60 out of 70) as good, apart from a small proportion (n=2), who showed poor behaviour during dental visit, in addition to eight children (11.4%) who showed satisfying behaviour, as shown in Table 4. Lastly, no significant (p>0.05) difference was found between the child’s behaviour during the study’s recall visit according to parental assessment, and caries experience based on dmft index.

Discussion

The prevalence of dental fear and anxiety in this study, based on the parental evaluation, was 40%. This is similar to the findings from a previous similar study, which was 39.6% according to parental assessment.14 Previous studies showed a similarity between the mean dental anxiety assessed by the children themselves and their parents.15 In this study the parental assessment of dental anxiety in their children used a dichotomously ‘yes/no’ single question. A previous study has shown that a single question has good validity, specificity, and sensitivity, and may be used with confidence to assess dental fear in such situations as national health surveys or in routine dental practice where a multi-item dental anxiety questionnaire is not feasible.10 The prevalence in this study was higher than in most of the previous studies examining an overall prevalence of dental anxiety (23.9%) in the population.16 This might be due to the study sample profile in a specialised paediatric dentistry department, in which more than half of the study sample had a dmft >2.7 and a history of invasive dental procedures (e.g., extractions, stainless steel crowns (SCCs), nitrous oxide sedation (N2O) or GA). This study showed a statistically significant relationship between dental anxiety and caries experience based on dmft/DMFT index according to WHO criteria (Table 2).13 This is plausible, as the literature has reported that children with a history of dental extraction are more fearful.17,18 This would be clinically important for caries prevention, as children with dental anxiety are susceptible to having worse oral health status.19 Consequently, a functioning recall system is important and should be maintained or improved if necessary.

Moreover, the current study showed a significant association between parental assessment of the oral health status of their children and caries experience according to dmft index (Table 4).12 Children with high and very high caries experience (dmft >4.5) were mostly evaluated as having either good or satisfying oral status, and only one child with high caries experience was evaluated with poor oral health status according to parental assessment. A high proportion of children (n=12) with moderate caries experience were still evaluated with good oral health status. This finding is supported by study evidence where the parental assessment of a child’s oral health status and the clinically determined oral status based on clinical examination have been found to be significantly different.20,21 Another study showed that caregivers overestimated the oral health status of their child, hence underestimating the treatment need.22 The findings of this study showed that parents potentially overestimated or even partially underrated their children’s oral health status according to the dmft index. This is clinically relevant since this significant variation might lead to an underestimation of the child’s treatment need, which may cause neglect of early caries prevention strategies.23 This aspect of this study sample is probably not relevant, as most of the children had already received dental treatment/rehabilitation (partially under sedation or GA) and were now in the recall phase, depending on caries experience assessment, two to four times a year.

Based on the results of the current study, a high proportion of children (n=60, 85.7%) behaved positively according to parental report during the dental recall visit, in which an application of a fluoride varnish with various tastes was implemented. This is similar to findings from previous studies, which showed that children preferred fluoride application with a pleasant taste and refused toothpaste with a bitter and medicated taste. Hence, the taste of a fluoride varnish is reported to be a predominant aspect influencing the acceptance of fluoride application in children.9,22,24

Conclusion

Dental fear and anxiety in children correlate with dental caries experience based on dmft index. The majority of children who attended for a dental follow-up appointment had moderate to very high caries experience. Interestingly, dental anxiety is still prevalent in recall children visiting a specialised paediatric university dental clinic, though these children had already received a variety of dental treatments. High caries experience was also associated with higher parent-reported dental anxiety and a poorer oral health status report.

Source of funding

This study was partially financially supported by VOCO GmbH, Germany.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)