Introduction

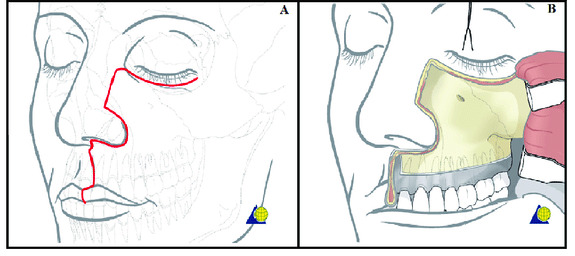

The maxillectomy patient presents unique challenges in terms of their surgical management and prosthodontic rehabilitation. Relative to other oral cavity subsites, maxillary tumours are less common. Between September 2021 and January 2023, out of a total of 120 oral cavity tumours (with 42 free flaps) managed surgically by the authors, only seven (6%) were maxillary tumours. Reconstruction of the midface is challenging given the anatomical complexity of the region and the need to restore function and aesthetics while ensuring en bloc resection of the primary tumour. Most commonly, maxillary tumours will present as a Brown Class 2 subtype with resultant oro-antral and oronasal communications (Figure 1, Table 1).1 The resultant defect, without appropriate reconstruction, can have a profound impact on patients in terms of nutrition, speech and psychological well-being. Reconstructive options can include non-surgical, surgical or combined modalities.2 These range from the use of an obturator prosthesis to free tissue transfer.

The use of zygomatic implants for reconstruction and rehabilitation post maxillary tumour ablation is well described. However, this technique does not address an oro-antral or oronasal communication, and resultant patient difficulties. First described in 2017, the zygomatic implant perforated (ZIP) flap facilitates rapid oral rehabilitation in the postoperative period prior to commencement of adjuvant treatment, where required.3 While not only providing good primary stability for an immediate prosthesis, it also closes any oronasal/antral communications and so seeks to combine some of the advantages of both a free flap and an implant-retained obturator. Herein we present the first three cases of ZIP flap reconstruction in our unit in St James’s Hospital. We hope this raises awareness, among the readership of this Journal, of the advances in reconstructive options available for their potential patients.

Case histories

Patient A

Patient A is a 66-year-old male who was referred by his general medical practitioner (GMP) with a large ulcer of the hard palate, which had been present for approximately six months. Relevant risk factors for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) included a 40-pack-year smoking history and prior excess alcohol consumption of 60-80 units per week. The patient was otherwise healthy with no regular medications and no known allergies. Following a biopsy for tissue diagnosis, relevant staging scans and discussion at the head and neck cancer multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT), it was recommended to proceed with surgical management of the tumour.

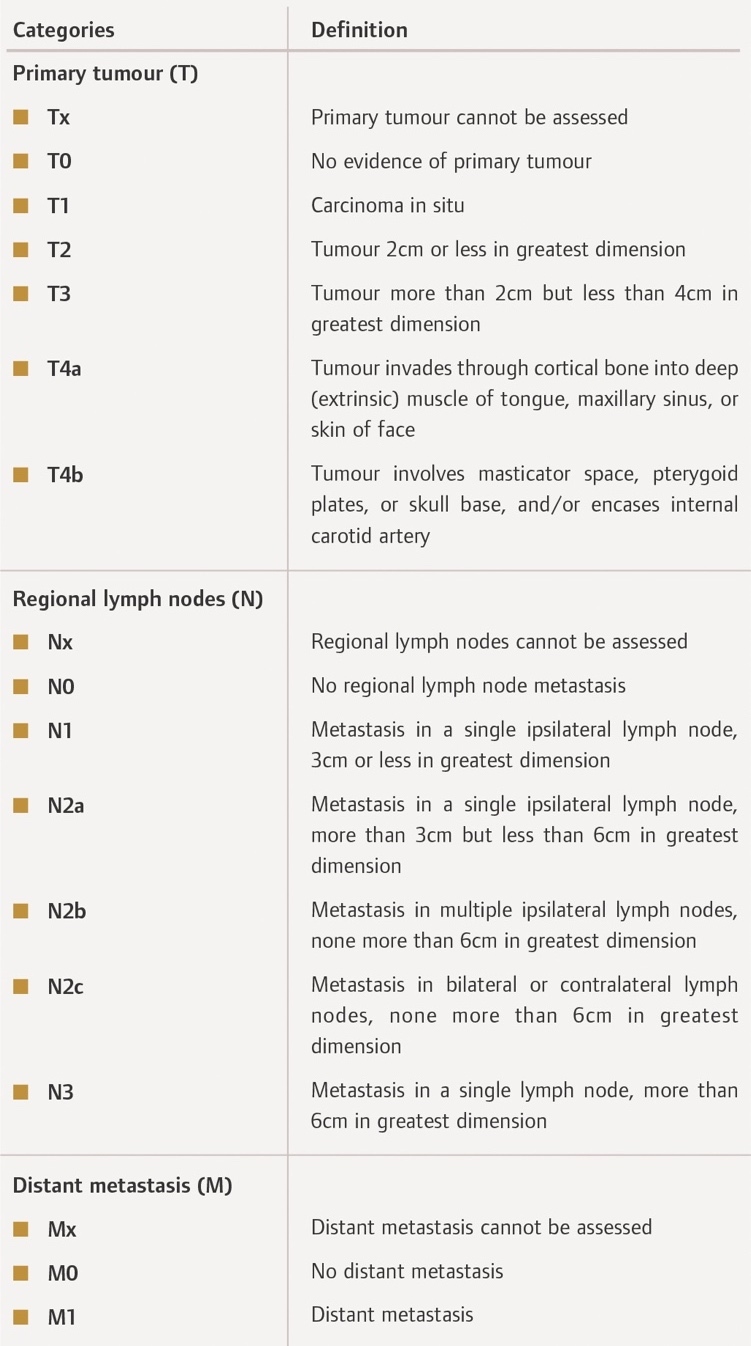

The patient underwent surgery in September 2022, which included a tracheostomy, sub-total maxillectomy, bilateral selective neck dissections, placement of two zygomatic implants on either side (four in total), and reconstruction of the defect with a right radial forearm free flap in a ZIP flap design. This was followed by a short postoperative stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) with subsequent ward-based care until discharge. The final pathological diagnosis was a pT4a pN0 MX OSCC with clear margins, as per the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumour Node Metastasis (TNM) staging system (Table 2). The date of prosthesis insertion was 21 days after surgery prior to the commencement of adjuvant treatment. Adjuvant treatment, recommended by the head and neck MDT based on the final pathology, consisted of 60Gy radiotherapy in 30 fractions, which the patient completed. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the primary tumour, intraoperative stages, and postoperative radiograph demonstrating implant positioning.

Patient B

Patient B is a 78-year-old female who was referred by her general dental practitioner (GDP) with a non-healing ulcer of the left posterior maxilla. Relevant risk factors for OSCC included longstanding oral lichen planus (OLP), which was being monitored by the patient’s dentist.6 The patient’s medical history was also significant for hypertension and primary biliary cirrhosis for which she takes amlodipine and ursodeoxycholic acid, respectively. She was a non-smoker with minimal alcohol consumption. Following a biopsy for tissue diagnosis, relevant staging scans and discussion at the head and neck cancer MDT, it was recommended to proceed with primary surgical management of the tumour.

The patient underwent surgery in November 2022, which included a left hemi-maxillectomy, left selective neck dissection, placement of two zygomatic implants on the left side and two dental endosseous implants in the anterior/right maxilla, and reconstruction of the defect with a left radial forearm free flap in a ZIP flap design. Once again, initial prosthesis impressions were taken by the maxillofacial prosthodontist during surgery. Following initial ICU care the patient recovered on the ward, with multidisciplinary rehabilitation involving speech and language therapy, clinical nutrition and physiotherapy. The final pathological diagnosis was a pT4 pN0 MX OSCC with clear margins of the left maxilla. The date of prosthesis insertion was 19 days after surgery prior to commencement of adjuvant treatment. Figures 4 and 5 show the primary tumour, resected specimen, ablative defect and final prosthesis. Figure 6 demonstrates the implant positioning on a postoperative orthopantomogram.

Patient C

This is an 79-year-old lady who initially presented with a non-healing oro-antral fistula following previous dental extraction. Examination and biopsy under general anaesthesia revealed an underlying SCC. Again, following discussion at our head and neck MDT, primary surgery was recommended for management of this tumour.

At operation, this lady underwent a left maxillectomy, left selective neck dissection, placement of two zygomatic implants on the ipsilateral side, placement of two standard endosseous implants in the anterior maxilla, and reconstruction with a radial forearm free flap, utilising a ZIP flap technique. She had an uneventful peri-operative course including a pre-planned ICU stay and transfer to the ward. Final pathological diagnosis was pT4 pN0 MX OSCC with clear margins, and placement of her fixed dental prosthesis was 21 days postoperatively. Figure 7 illustrates the primary tumour, resected specimen, ablative defect and ZIP flap. Figure 8 shows the orthopantomogram demonstrating the position of the zygomatic/dental implants for patient C, while Figure 9 shows the final prosthetic result for this patient.

ZIP flap technique

Surgical technique

The maxillary tumour is accessed and ablated in standard fashion, via a transoral approach or a Weber-Ferguson access procedure if required (Figure 10). A radial forearm free flap is raised, but not detached from its pedicle, in standard fashion concurrently. The maxillary defect is assessed and in particular the zygomatic arch/bone examined to ensure sufficient residual bone for zygomatic implant placement. In patient A, four zygomatic oncology implants (Southern Implants; South Africa) were placed: two on the left and two on the right. In patient B, two zygomatic implants were placed into the left zygoma, with two standard endosseous dental implants in the right anterior maxilla. Good primary stability was noted in all implants.

The radial forearm flap is then disconnected from the arm and draped into the defect standard fashion. The pedicle is transferred via a soft tissue tunnel to the ipsilateral neck and a microvascular anastomosis of both artery and vein is performed standard fashion. The flap is then ‘inset’ using standard interrupted vicryl sutures to seal the oro-antral/nasal communication. The underlying zygomatic implants are then palpated and the flap carefully perforated in these areas to allow the implant abutments into the neo-oral cavity. This is done with sharp dissection through the skin and blunt dissection to the abutments themselves. A perforated polythene washer is then placed between the conical abutment protection caps and the skin of the flap to ensure that the implants do not disappear or get ‘swallowed’ underneath the flap during a phase of postoperative swelling.

Prosthodontic technique

Presurgical prosthodontic care involves meeting with the patient to discuss the prosthetic pathway, and making preliminary impressions to facilitate fabrication of implant surgical guides, a surgical prosthesis if indicated, custom trays, and a jaw relation record. The presurgical meeting is a critical interaction both from a technical point of view and, very importantly, from a human interactive point of view. If another family member can be present, it can be extremely beneficial in terms of information appreciation.

Unilateral zygomatic implants, by nature of their length, may be unstable, especially if there is no alveolus remaining. Utilisation of regular endosseous implants may benefit the stability in terms of creating tripodisation. Quad zygomatics may achieve their own bilateral stabilisation through early splinting. In these cases, there were some lower teeth, which were beneficial in terms of keying a surgical guide, and in terms of recording a jaw relation at the time of surgery. Upper and lower Essix retainers were made on the preoperative casts or on the diagnostic wax-up tooth position casts. The retainers were joined together with cold cure acrylic at the vertical dimension of occlusion. These joined retainers were then used as the guides for implant placement.

The prosthetic technique is to take the impression at the end of the operative procedure, when the flap has been installed and the microvascular anastomosis is complete. Custom tray and polyvinyl siloxane impression material are used. The zygomatic implants are splinted with light-cured acrylic intraoperatively to avoid any distortion at impression making. Multi-unit abutments are used to facilitate compensation for any angular discrepancies. After the impression, healing abutments are placed over the multi-unit abutments, and a jaw relation record is recorded against the abutments. If there are remaining teeth, these may facilitate the jaw relation. If there are no remaining teeth, but some remaining palate, the palate may facilitate the jaw relation. If it is anticipated that there will be no or minimal remaining maxilla post resection, a preoperative face marking is carried out with surgical marker, placing skin marking points at the glabellum and menton. A ruler measurement of vertical dimension of occlusion is recorded, and then applied at the end of the operation to record the jaw relation.

Postoperatively, the impression is boxed, beaded and poured in type IV stone. Healing abutments are placed on the multi-unit abutment analogues, and the intra-operative jaw relation record is used to mount the casts. A tooth position wax-up is placed on the cast as the guide for the laboratory fabrication of a titanium bar. When the bar is ready, teeth are applied in wax, and the bar is tried in to confirm fit, jaw relation, and aesthetics. It is processed and delivered in a timely manner. The goal is to provide a fixed restoration within about three weeks, to take advantage of the early stability of the implants. The early fixed restoration offers a splinting mechanism, which is essential for the zygomatic implants. Early restoration also facilitates the fabrication of very stable radiotherapy stents if required.

Discussion

Maxillary malignancy is most frequently confined to the alveolus and antral walls, with resultant ablative defects potentially impacting several aspects of the patient’s quality of life, including nutrition, speech, and body image.8 Relative to other sites in the oral cavity, these tumours may also be associated with a poorer prognosis, so timely diagnosis and treatment are essential to optimise patient outcomes.9

Prior to the advent of routine microsurgical reconstructive techniques and reliable osseointegrated implant technologies, the functional and aesthetic outcomes for patients undergoing midfacial oncologic resections were sub-optimal. Previously, prosthetic obturators were the mainstay of treatment in reconstructing maxillary defects. However, issues with patient comfort, retention and incomplete oronasal seal can negatively impact the patient’s quality of life. The performance of these prostheses could also be further impeded by the effects of adjuvant radiation therapy on adjacent bone and soft tissue. Despite this, obturation alone without another form of reconstruction may be, in selected cases, the most appropriate form of rehabilitation.

Free tissue transfer is now regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for reconstruction of head and neck ablative defects.10–12 For maxillary tumours, the choice of soft tissue only (e.g., radial forearm free flap) versus composite (e.g., fibula free flap) will depend on a variety of factors, including size of the defect, need for dental rehabilitation, and surgeon preference.10 In a Brown Class II maxillary defect, where the orbital rim and floor, and zygomatic arch, are preserved, the need for reconstruction using a composite (bone and soft tissue) free flap is questionable. In such cases, the priorities are safe tumour ablation, closure of oro-antral/nasal communication, and provision of teeth and commensurate soft tissue support. While obturation alone can address some of these problems, issues related to stability, lack of oronasal seal, and ongoing denture maintenance persist.

The ZIP flap, described by Butterworth and Rogers in 2017, is a unique free flap design that seamlessly combines free tissue transfer with prosthodontic rehabilitation at the time of surgery. Perforation of the flap’s soft tissue with zygomatic implants at the time of surgery allows for immediate fabrication of a customised prosthesis. Multidisciplinary involvement of the maxillofacial prosthodontist is essential in terms of surgical planning, implant positioning, and facilitation of initial prosthesis impressions intra-operatively. Conventional zygomatic implants in non-oncology patients have been shown to have good survival rates and, more recently, evidence has emerged supporting the use of these implants in head and neck oncology patients.8,13,14

The key advantages of the ZIP flap are that it not only separates the oral cavity from the sinuses and/or the nose, but it also simultaneously provides a supra-structure for a definitive fixed prosthesis. Additionally, and crucially, patients are in a position to receive their prosthesis prior to commencement of adjuvant radiotherapy, which carries with it challenges such as trismus, mucositis, and tissue fibrosis. Where resection involves large portions of the anterior maxilla, consideration may be given to bony reconstruction with a composite flap (e.g., fibula free flap), to restore continuity of the premaxilla and prevent collapse of the upper lip post radiotherapy.

The majority of patients with midface tumours have advanced-stage disease and therefore potential reduced overall survival. It is important, therefore, that the quality of life of this cohort is maximised in a timely fashion. ZIP flaps facilitate restoration of the dentition within three to four weeks of surgery.

Conclusion

The ZIP flap has been shown to be a safe and reliable method of reconstruction for post-ablative midface defects. Advantages of the technique are that it provides predictable closure of surgical defects and allows for immediate fabrication of a customised, fixed dental prosthesis. As a result, patients can achieve adequate oral rehabilitation prior to proceeding to adjuvant treatment, where required. With careful patient selection and planning, the technique may ultimately be regarded as the standard of care in the management of low-level maxillary tumours.

.__243154_.png)

.__243154_.jpeg)

__resected_specimen_(b)__ablative_defect_(c.png)

__resected_specimen_(b)__and_ablative_defec.png)

__post-ablative_defect_(b)__zygomatic_.png)

.__243154_.png)

.__243154_.jpeg)

__resected_specimen_(b)__ablative_defect_(c.png)

__resected_specimen_(b)__and_ablative_defec.png)

__post-ablative_defect_(b)__zygomatic_.png)