Background

Class II malocclusion, which affects nearly 25% of 12 year olds in the UK, is the most commonly treated malocclusion in the HSE orthodontic service.1,2 The 2002 Irish Children’s Oral Health Survey found that 12.2% of 12 year olds have an overjet of 6mm or greater and 2.5% have an overjet of 10mm or greater.3 The aetiology can be skeletal, dental, or both. Mandibular retrognathia and prominent maxillary incisors are typical features.4 Along with posing an increased risk for trauma to the maxillary incisors, this malocclusion has also been associated with an elevated incidence of bullying.4,5 Treatment often includes growth modification with a functional appliance, followed by fixed appliances to align the teeth orthodontically.4

A wide range of functional appliances are available to correct Class II malocclusions, including removable functional appliances, such as the Bionator and Fränkel appliances, and the fixed Herbst appliance. The Clark’s twin block appliance, favoured among UK orthodontists, is the functional appliance used primarily within the department where this service evaluation was conducted.6,7 A twin block appliance is a removable appliance consisting of maxillary and mandibular acrylic blocks, which posture the mandible forward on closure. It is well established in the literature that the changes brought about by twin block appliances are primarily dentoalveolar in origin, but they can also improve profile and lip competence in children with a Class II skeletal pattern.8,9 O’Brien et al. (2003) established, through a randomised controlled trial, that using a twin block appliance results in 1.9mm of additional skeletal growth. Tulloch (1997) found even smaller results of 1.33mm.10,11 Furthermore, Mills (1998) found that this additional skeletal growth occurs primarily in the vertical direction, facilitating a reduction in overbite rather than overjet.12

The timing of use in relation to patient growth is critical in determining the effectiveness of functional appliance therapy.13 The rate of mandibular growth is not constant throughout childhood and adolescence, with the existence of a pubertal peak well established in the literature.14 While the onset and duration of the growth spurt varies among individuals, it generally occurs at 11.89 years in females and 13.91 years in males.15 It has been shown that functional appliance therapy is most effective when the peak of mandibular growth occurs within the treatment period, with treatment commencing in the pre-pubertal phase.13,16 There is also some evidence that compliance is better in younger cohorts.17,18 O’Brien (2003) found that functional appliance discontinuation rates among adolescents were twice that of pre-adolescent treatment groups (33% vs 16%).10 Better patient compliance among younger cohorts should lead to improved treatment outcomes. Finally, Rizell (2006) argued that pre-adolescent treatment with a functional appliance may reduce treatment duration in the fixed appliance stage".19

The HSE orthodontic service is mandated to provide treatment for those with the highest orthodontic treatment need. A modified Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN) score has been used in the HSE for the past 15 years to determine treatment eligibility. Only patients with a dental health component score of 5, or selected grade 4s, are eligible.2 Children typically have their orthodontic assessment in their final year of primary school, when they are approximately 12 years old. Those deemed eligible for treatment can then face long waiting lists. At the end of 2019, there were 19,216 patients on orthodontic treatment waiting lists across Ireland. Over 25% of these patients had been waiting over three years for treatment.20 Unless children are targeted and prioritised, they may miss the window of opportunity for growth modification treatment in the public service setting.

This service evaluation was carried out in a HSE orthodontic clinic, where an effort has been made in recent years to prioritise patients classified as 5a on the IOTN for earlier treatment. IOTN grade 5a indicates the presence of an overjet greater than 9mm prior to beginning treatment.21 Rather than being placed on a waiting list, patients deemed eligible for orthodontic treatment under the 5a classification would start treatment expeditiously following their sixth class screening. These patients would start treatment approximately two years earlier than those placed on a waiting list, making them 11 or 12 years old starting treatment compared to those coming from the waiting list, who would be at least 13. This prioritisation system is unique to this individual HSE orthodontic clinic.

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of this prioritisation by comparing the treatment duration and compliance of two cohorts of children treated with twin block appliances: those who were 11 or 12 when treatment started compared to those who were 13 or 14 at the start of treatment.

Methods

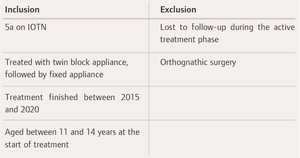

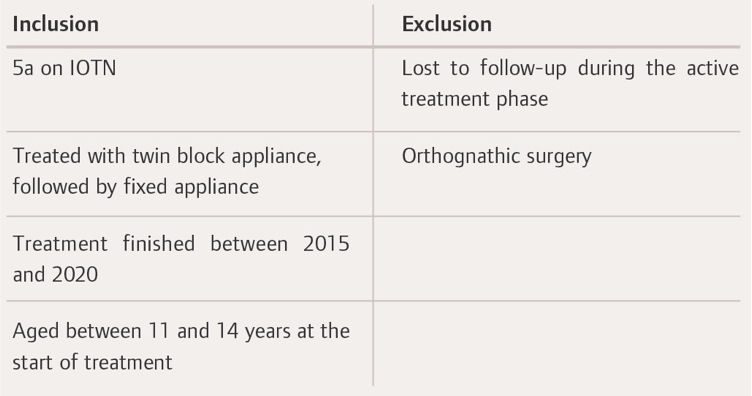

This service evaluation was carried out in a large HSE orthodontic department in the west of Ireland. It services a population of patients from both rural and urban environments, who have a demographic make-up similar to that of the rest of Ireland.22 The methodology for this service evaluation is in keeping with the Health Research Regulations 2021.23 The population was divided into two groups: a prioritised treatment group (PTG), who started treatment at age 11 or 12; and, a routine treatment group (RTG), who started treatment at age 13 or 14. Age ranges were chosen by a consultant at this clinic to be representative of those who have received treatment in a routine timeframe (RTG) and those who would have received treatment in a prioritised timeframe (PTG). The sample for this study was obtained by screening the records of children who had finished treatment between 2015 and 2020. The chosen time frame encompasses the period before and after the implementation of the prioritisation system in 2017, ensuring the acquisition of a sufficient cohort from both groups. The selection criteria are summarised in Table 1. The sample was generated from the first 100 patients from each cohort to meet the inclusion criteria. Orthotrac was used to screen the records of 557 patients for sample selection. Patient records were screened, and the following data was extracted:

-

duration of twin block treatment;

-

duration of fixed appliance treatment;

-

total treatment duration; and,

-

compliance with twin block wear.

All patients were treated by either a consultant orthodontist, specialist orthodontist, or orthodontic therapist under the guidance of a consultant orthodontist. Patients undergoing twin block treatment were instructed to undergo full-time wear protocols, in which the functional appliance was only removed for eating and sports. The duration of the twin block treatment was measured from the date the twin block was fitted to the date that fixed appliances were bonded. The duration of fixed appliance treatment was measured from bond up to debond.

Clinical entries in the electronic patient records were reviewed, and each instance of poor compliance was documented. Each of these instances were counted as compliance issues. The total number of compliance issues for each patient was then calculated. Discussions regarding inadequate wear of appliances, instances of lost appliances, poor oral hygiene and failure to attend appointments were all regarded as instances of poor compliance. These markers of compliance were adapted from a study by Mandall et al.24

A statistical analysis was carried out using Microsoft Excel XLSTAT. A two-sample t-test was used to determine the statistical significance of the treatment duration data collected, while regression analysis was used to determine the significance of the compliance count data. Both were calculated with a significance level of 95%.

Results

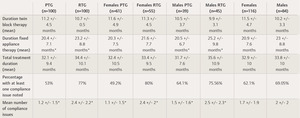

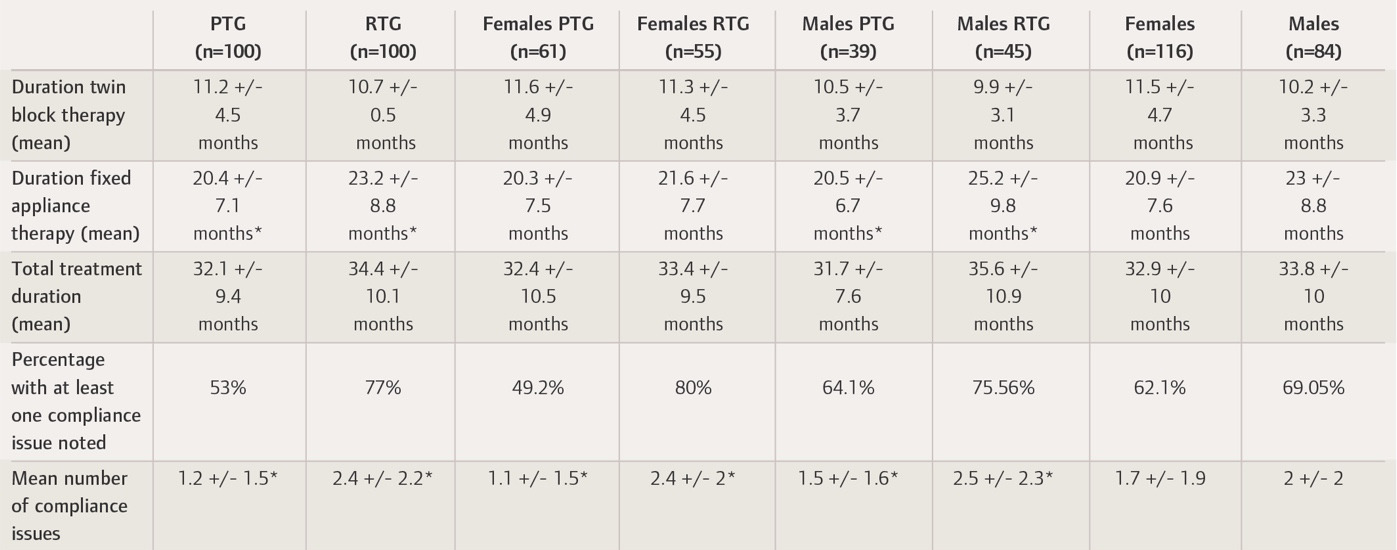

The PTG consisted of 61 females and 39 males, with a mean age of 12.3 years +/- 0.29. The RTG consisted of 55 females and 45 males, with a mean age of 13.8 +/- 0.42 (Table 2).

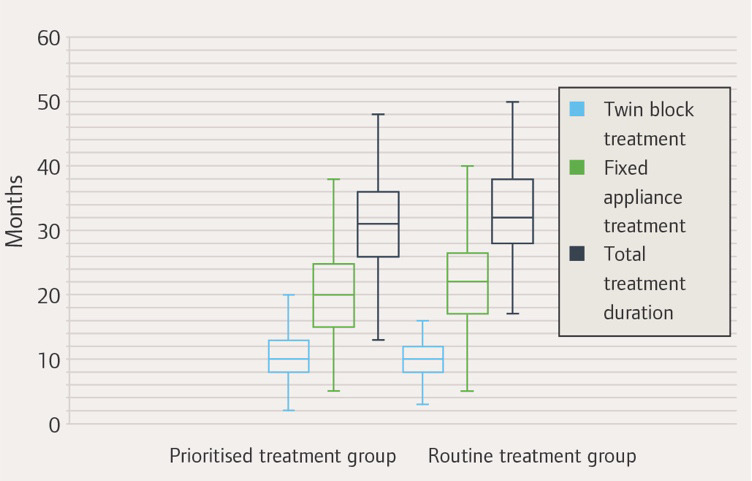

Total treatment time was shorter in the PTG than in the RTG (32.14 vs 34.41 months). However, this difference was not statistically significant. A statistically significant difference was found between the two cohorts’ mean duration of fixed appliance therapy (Figure 1). This was shorter in the PTG than in the RTG (20.37 months vs 23.24 months, P=0.01). A total of 53% of children in the PTG had at least one compliance issue noted, with a mean number of compliance issues of 1.24 per child. Compliance was worse in the RTG, affecting 77% of children, with a mean number of 2.43 (Figure 2). This difference was statistically significant (P=0.00004). These results were consistent across both genders (Table 2).

Discussion

This service evaluation aimed to assess how prioritisation of patients requiring functional appliance therapy for earlier intervention affects the course of their treatment. The goal of prioritising patients for growth modification would be to reduce the complexity of future treatment and improve patient compliance. Overall, this service evaluation found some evidence to suggest that a younger age at the start of twin block therapy can be used to predict better patient compliance and a reduced duration of fixed appliance treatment. The overall treatment time did not significantly differ between the PTG and the RTG, however, suggesting that the age at which patients receive twin block appliance treatment within the 11- to 14-year range may not have a significant impact on the overall treatment duration.

Both the PTG and RTG had longer mean total treatment durations than those found in similar studies. Dyer et al. (1991) conducted a retrospective study of patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusions and found a mean treatment duration of 29.52 +/- 4.32 months.25 A similar study by O’Brien et al. (1995) found a mean treatment duration of 33.7 ± 10.4 months for two-phase treatment of Class II Division 1 malocclusions in adolescents.26 O’Brien (2003) looked at treatment duration for treatments involving both functional and fixed appliances, and found a mean duration of 21.99 months.10 This prolonged treatment duration may be because this service evaluation was conducted in a public orthodontic clinic. Mavreas et al. (2008) found that treatment duration increases with the severity of the malocclusion.27 The severity of malocclusion is a significant factor in determining eligibility for orthodontic treatment under the HSE. All patients in this study had an overjet of at least 9mm, likely predisposing them to longer than standard courses of treatment. Some patients included had treatments spanning the year 2020. Clinic closures during the Covid-19 pandemic, and the cancellation of appointments due to patient, parent, or staff isolation requirements, may have prolonged treatment for these patients. Nevertheless, while patients in the PTG were not found to have a shorter total treatment duration, the duration of fixed appliance therapy was significantly shorter for the PTG. This may still be clinically significant, representing a reduction in treatment cost and in the risks associated with fixed orthodontic appliances, including demineralisation of enamel, root resorption and periodontal condition.

Furthermore, evidence was found that those in the PTG had better compliance with treatment than those in the RTG. Compliance, as measured retrospectively by the number of clinical entries indicating poor compliance, is prone to bias. This is due to the inherent subjectivity in noting compliance, and intra-operator differences in notetaking style and level of detail. Moreover, although the compliance indicators employed have been utilised as proxy metrics for compliance in previous research, they do not directly quantify the duration of appliance usage. In order to acquire a more precise evaluation of compliance with twin block wear, it would be optimal to incorporate objective measures, such as electronic monitoring devices that record appliance usage. Nevertheless, considering the constraints imposed by the accessible data retrospectively, the employed compliance measures can still offer valuable insights and support the conclusions pertaining to patient age, compliance, and treatment duration.

Failure to complete treatment may also indicate poor compliance. Therefore, excluding those lost to follow-up could represent an additional source of bias if the number of patients lost to follow-up was disproportionately different between the two cohorts. Clear results indicating greater compliance within the PTG than in the RTG were demonstrated across both genders. These results are in line with previous studies. For example, Schäfer et al. (2015) found that when instructed to wear a removable orthodontic appliance for 15 hours a day, patients aged 10 to 12 would wear it for a mean of 9.8 hours a day, while patients aged 13 to 15 would wear it for a mean of 8.5 hours a day.18

Skidmore et al. (2006) found that poor compliance leads to increased treatment times, with poor oral hygiene alone adding 2.2 months to treatment.28 Additional studies of broken appointments and damaged appliances support this finding.24,25 To this point, it is difficult to say whether reduced patient compliance or an increased treatment complexity linked to older age leads to longer fixed appliance treatment durations in the RTG. Further study would be required to test this, including the assessment of pre-treatment malocclusion severity.

While all patients studied in this service evaluation completed treatment, no outcome measure was recorded. This may represent a source of bias if disproportionate numbers from one cohort finish treatment with a residual need. A future study could be carried out prospectively, allowing consideration for variables such as malocclusion severity, along with the measurement of an objective outcome.

Furthermore, this service evaluation only looked a numerical age; no skeletal maturity staging was carried out. Skeletal maturity staging helps to determine the optimal timing for growth modification, by identifying the pubertal growth spurt. The inclusion of skeletal maturity staging would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how the timing of treatment initiation, relative to skeletal maturation, affects treatment outcomes.

Another limitation of this service evaluation is the sampling method used. The first 100 patients from each cohort to meet the inclusion criteria were included in the sample. This non-random sampling technique could bias the data if a non-representative sample was chosen. Furthermore, the limitation of inclusion criteria to patients who had a course of functional and fixed appliance treatment excludes those successfully treated with a functional appliance to the point that fixed appliance treatment was unnecessary. Finally, as stated previously, statistically significant differences do not necessarily translate into clinically significant differences. This needs to be considered when interpreting the data.

Conclusion

Prioritising patients who require functional appliance treatment does not reduce the total treatment duration. A correlation between earlier treatment, improved patient compliance and a shorter course of fixed appliance therapy can be seen. This is potentially clinically significant as it indicates a possible reduction in treatment expenses and risks related to fixed orthodontic appliances. Thus, support can be seen for treatment with functional appliances at age 11 or 12 rather than older. This highlights the importance of both timely referral and treatment prioritisation for patients requiring growth modification. As this is observational research, causation cannot be proved. Further prospective research is needed in this area to add to the body of evidence. A recent high-quality, randomised control trial by Mandall et al. (2023)29 could be used as a template for future research in this area.