Introduction

A pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign inflammatory hyperplastic lesion located in the skin and the mucous membrane.1 In the oral cavity, PGs have a higher propensity to present in females, especially in their second decade, during pregnancy, and after menopause.1,2 PGs are more commonly observed in the maxilla than the mandible, and in the anterior rather than the posterior region of the oral cavity.3 It appears under a microscope as a highly vascular proliferation that resembles granulation tissue.4

Numerous studies have tried to reveal the aetiology of PGs; however, the exact aetiology remains unclear.5 The commonly reported causes are local irritation and chronic trauma, which are responsible for initiating reactive lesions characterised by connective tissue proliferation.6 Other causes may include poor oral hygiene, parafunctional habits, a history of dental extraction, and overhanging dental restorations.5,7 In addition, medications such as calcium channel blockers, and anticonvulsant and immunosuppressant drugs, are known to induce gingival hyperplasia.8 Other researchers believe that PGs appear because of an infectious process or hormonal changes.9

A PG diagnosis depends on a biopsy and histopathological assessment, which help to differentiate from other common oral diseases.10 Its differential diagnosis includes haemangioma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, hyperplastic gingival inflammation, pregnancy tumour, peripheral ossifying fibroma, drug-induced gingival hyperplasia, and malignant lesions.11 However, the aggressive behaviour of a PG can be diagnostically challenging.12

The treatment of choice for a PG is an excisional biopsy.4 Other treatment modalities include cryosurgery. The use of an Nd:YAG laser, flash lamp pulsed dye laser, injection of ethanol or corticosteroid, and sodium tetradecyl sulphate sclerotherapy has also been documented.4

This article aims to present the case of a patient who attended the dental clinic while complaining about a large, rapidly growing intraoral mass with aggressive behaviour, which had manifested as an extensive loss of alveolar bone, as well as mimicking a malignant lesion. The article will also compare this case with current reported cases of aggressive PGs in the literature.

Clinical presentation

A 50-year-old male was referred by his general dentist in a private dental clinic to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department at King Fahad Hospital (KFH) in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. The referral was for a large lump that needed further evaluation and treatment. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for controlled diabetes and hypertension. His medications included long-acting insulin and rapid-acting insulin analogues for diabetes mellitus. The patient took calcium channel blockers and long-acting angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for hypertension. The patient had been a smoker of two packs per day for more than 25 years. The lesion had developed for almost a month and a half before the first visit.

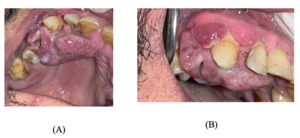

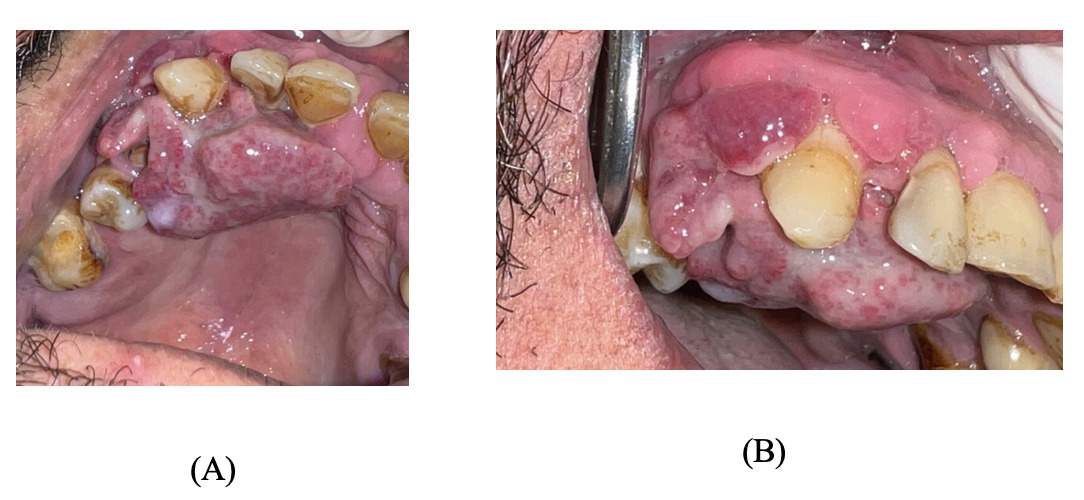

Upon extra-oral examination, no abnormalities were detected. Intra-oral examination revealed a large, exophytic, rapidly growing, soft swelling with an irregular surface extending from the upper right central incisor to the upper right first molar, causing rapid expansion of the buccal and palatal alveolar bone (Figure 1).

When palpated, the swelling was soft, compressible, and bled easily. Grade III mobility was associated with the upper right lateral incisor, upper right canine and upper right first premolar. In addition, grade II mobility was associated with the upper right central incisor, upper right second premolar, and upper right first molar. The patient was not in pain, but felt discomfort due to the rapid growth of the lesion. In addition, the presence of the lesion made it difficult for the patient to maintain oral hygiene, thereby favouring the lesion’s growth.

The patient denied having unexplained pain, fevers, lymphadenopathy, persistent cough, hoarseness, swallowing difficulty, loss of appetite, night sweats, or numbness in the lesion’s area, or any other warning manifestation that might raise the index of suspicion for malignancy.

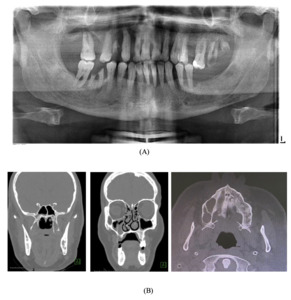

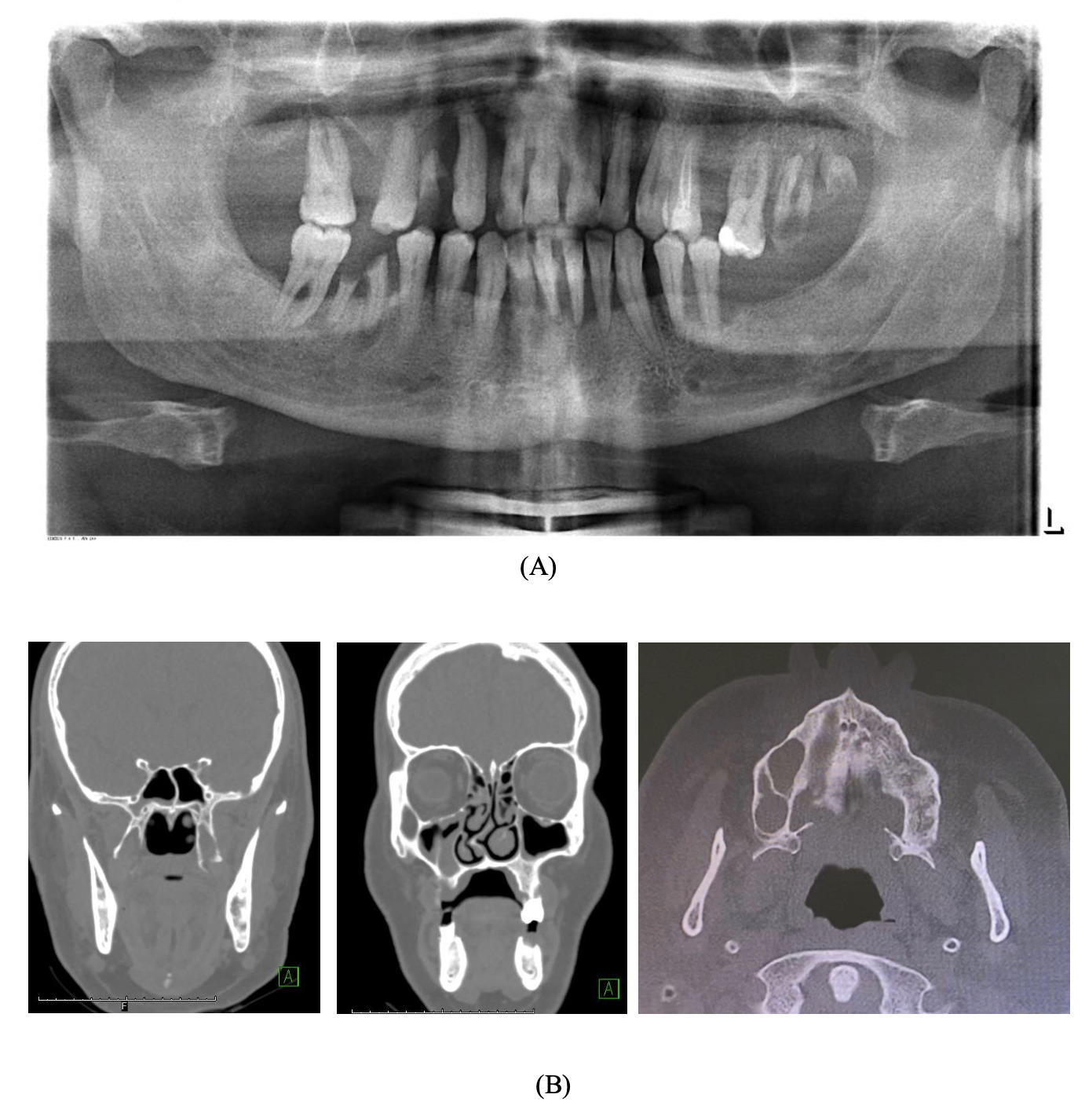

A pre-operative orthopantomogram (OPG) showed multiple non-restorable teeth in both jaws, as well as generalised, horizontal moderate to severe bone loss (Figure 2a). Pre-operative cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) showed an ill-defined lesion on the palatine process of the right maxillary and alveolar bone (Figure 2b).

Management

The treatment plan was discussed with the patient and began with advising him to quit smoking and participate in a smoking cessation programme. Thereafter, an incisional biopsy of the lesion was performed under local anaesthesia to detect the precise diagnosis. The surgical site was sutured using polylactic acid suture 3/0. The biopsy was sent to the histopathology laboratory, and following histopathological assessment (Figure 3), the diagnosis was of a PG.

Definitive treatment included a complete excision of the lesion from the buccal and palatal aspect associated with extraction of all hopeless teeth (upper right lateral incisor, upper right canine, upper right first premolar, upper right second premolar, and upper right first molar). Curettage and alveoloplasty were performed, followed by irrigation and haemostasis achieved by suturing to promote primary healing (Figure 4).

Postoperative instructions were given (i.e., maintain good oral hygiene and a soft diet, and avoid spitting in the first 24 hours), and antibiotic coverage of amoxicillin 500mg three times daily for seven days, as well as painkillers, was prescribed. The patient tolerated the procedure without complications and was discharged on the same day.

The patient attended his recall visits (at one week, three weeks and one year postoperatively). Clinical examination showed sufficient healing with no signs of recurrence or infection (Figure 5).

Discussion and review of the literature

The current case report was conducted based on the CARE (CAse REport) Checklist developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) at the University of Adelaide, South Australia. Ovid, Medline and Embase (1946 to 2022) were searched for relevant articles related to an aggressive PG. Clear search strategy keywords (i.e., pyogenic granuloma.mp. or granuloma, pyogenic, aggressive granuloma.mp., aggressive.mp., and a combination of these keywords) were used to search the relevant articles. Three evaluators worked independently to include or exclude the relevant studies. All types of studies in the English language were included from 1946 to January 14, 2022. Only 12 articles were found to be related to aggressive PG. Ten of these were case reports (Table 1),11–20 one was a review (Table 2),3 and one was a retrospective study (Table 3).21

Site of PG

Similar to the current case, five case reports reported that the site of the PG was in the maxilla.12,13,15,17,19 In the remaining five case reports, the PG was reported in the mandible.11,14,16,18,20 One review included in this article discussed PGs and found that the location of the majority of included cases was the posterior part of the mandible without bone loss.3 In addition, a retrospective study showed a site of a PG associated with a dental implant.21

Treatment modalities

In our case report the treatment of choice was an excisional biopsy under local anaesthesia as well as the extraction of hopeless teeth that were associated with the lesion. Similar to the current case, three case reports were found to treat a PG by means of an excisional biopsy.16,19,20 In one case, the treatment was oral prophylaxis followed by teeth extraction and an excisional biopsy.11 Another case used an incisional biopsy followed by an excisional biopsy after the histopathological report.17 Two other case reports used antibiotics after an excisional biopsy without teeth extraction.15,18 One case report outlined treatment of localised aggressive periodontitis combined with an excisional biopsy.15 Additionally, one of the included case reports was that of an excisional biopsy with extraction of the affected teeth without oral prophylaxis.12 What is more, chlorhexidine mouthwash was used for two weeks to decrease the lesion size, and then an excisional biopsy after one month was also reported.14 In addition, a bone trough was reported as a method of management.20 The included review in the data analyses illustrated 16 cases of PGs, with successful treatment including an excisional biopsy and curettage.3

Aggressive pyogenic granuloma

The current case presented a diabetic and hypertensive patient, who attended the dental clinic while complaining about an aggressive lesion. Our case, supported by other reported cases in the literature, showed that an aggressive PG could appear clinically as an irregular soft lesion, purple and reddish and bleeding easily, with resorption of the alveolar bone. On the other hand, the clinical picture of a PG is often characterised as an asymptomatic, painless lesion covered by a yellow fibrinous membrane that grows slowly without bone loss.10 In addition, an aggressive PG can be associated with mobile teeth in the lesion area.

The appearance of the aggressive PG in our case report is similar to that of aggressive PG developing in association with dental implants. For example, Jané-Salas et al. (2015) emphasised in their review that aggressive PG is associated with cases that include dental implants.3 Similarly, in their retrospective study, Shuster et al. (2021) found that aggressive PG was represented at 25%, with a recurrence rate of 6% when it was associated with dental implants.21

Conclusions

A PG could exhibit aggressive behaviour that mimics malignant lesion behaviour, with fast growth, rapid expansion of the buccal and palatal bone, bleeding, and alveolar bone loss associated with mobile teeth. Aggressive PGs were reported to be more commonly associated with dental implants, mimicking peri-implantitis. Histopathological assessment is essential in order to exclude any potential malignancy and help with early referral to formulate a definitive diagnosis and treatment plan.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge histopathology consultant Dr Nasir Al-Noor at King Faisal Hospital (Makkah, Saudi Arabia) for his contribution to this project by reporting and reading the histopathological slides.

__extraction_of_the_h.png)

__three_weeks_(b)_and_one_year_(c)_after_the_operation__showing_good_healing_w.png)

__extraction_of_the_h.png)

__three_weeks_(b)_and_one_year_(c)_after_the_operation__showing_good_healing_w.png)