Introduction

Endodontic treatment techniques have been evolving over the last few decades, including improvement in instrumentation and obturation techniques, which provide more accurate and faster outcomes. However, the complications of such techniques can be serious and lead to unfavourable results.1–3 In this case report, we present an extremely rare complication affecting the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) post root canal overfilling and extrusion.

During root canal obturation, where the apices of teeth are intimately related to the mandibular canal, the extrusion of sealer into the mandibular canal can cause nerve injury both mechanically and chemically.2,3 Mechanically, injury results from a traumatic compression of the nerve within the inferior alveolar canal.4,5 Furthermore, chemical neurotoxic effects may arise from the constituents of the endodontic obturation materials.6–8

Although spontaneous nerve recovery can occur after root canal sealer extrusion with pharmacological agents, in some cases, surgical removal and debridement of the sealer from the mandibular canal can result in almost complete resolution of nerve symptoms.7

In this article, we report on the surgical treatment of a patient with paraesthesia following an IAN injury caused by the extrusion of a large amount of root canal filling material (AH Plus sealer) into the mandibular canal.

Case report

A 42-year-old female teacher was referred to the oral and maxillofacial surgery service at University Hospital Galway by her general dental practitioner (GDP) after an incident during which she underwent root canal treatment of the lower left first molar. Medically, the patient has a history of multiple sclerosis (MS) and she was a non-smoker.

The patient presented ten days after obturation with severe pain and complete paraesthesia of the left side of her lower lip and chin area. The patient reported that she had immediately developed pain in the region of the distribution of the left IAN and paraesthesia after undergoing the endodontic treatment. According to her dentist’s explanation, the treatment consisted of canal instrumentation using a rotary preparation system, irrigation with sodium hypochlorite, EDTA 17% solution and chlorohexidine, and obturation with gutta-percha using a warm vertical obturation technique with AH Plus root canal sealer.

The patient was initially treated with a steroid (prednisolone 40mg), paracetamol with codeine, and vitamin B12. Vitamin B12 is utilised to promote neurosensory recovery in peripheral neuropathy and to treat nerve injuries resulting from oral surgeries, such as third molar removal, dental implant placement, local anaesthesia, or trauma.9 However, this medication had no effect on the symptoms.

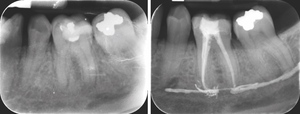

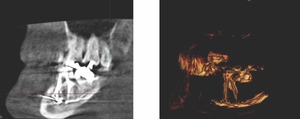

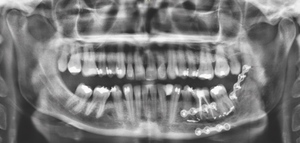

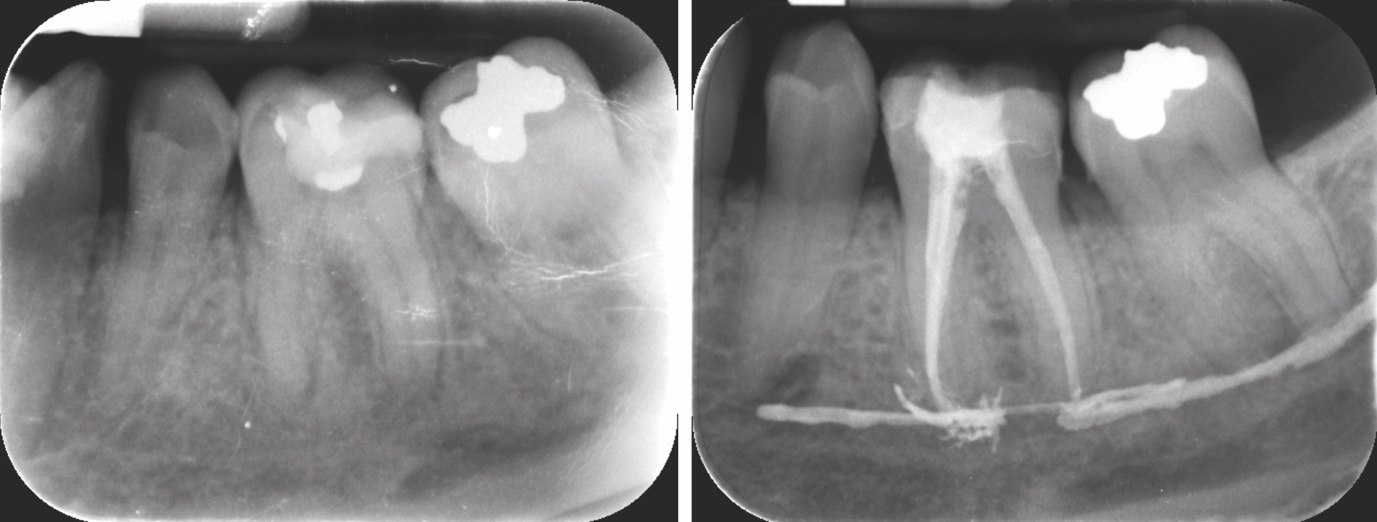

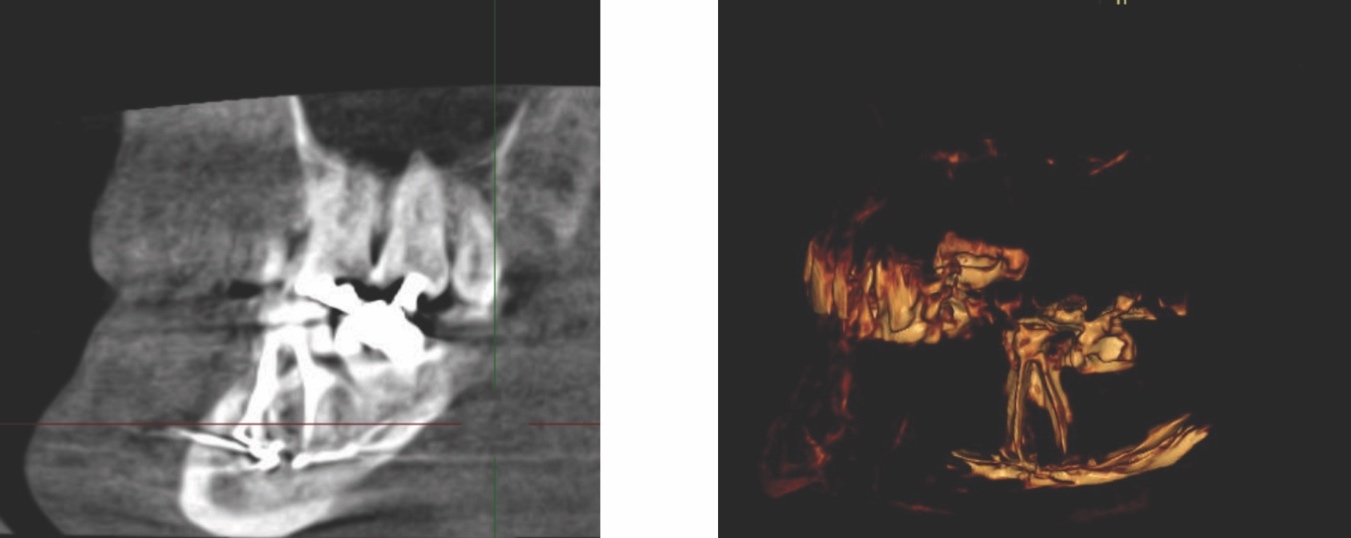

Radiographic examinations consisted of digital orthopantomogram (OPG), peri-apical (PA), and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans. The scans revealed that the lower left first molar root canals were obturated with a radiopaque material, and showed root canal filling extending beyond the apices of the tooth and approximately 5cm along the mandibular canal (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

The causes of lip paraesthesia in this case were either chemical injury or pressure injury due to compression of the nerve inside the canal. The decompression of the nerve and subsequent nerve lateralisation were discussed with the patient in detail, including the risks and benefits of the surgery.

Treatment

The patient commenced treatment with steroids and vitamin B12 before surgery. However, patient uncertainty about the surgical option delayed the intervention for approximately four weeks.

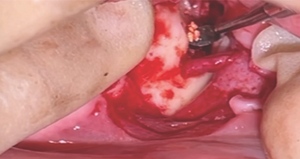

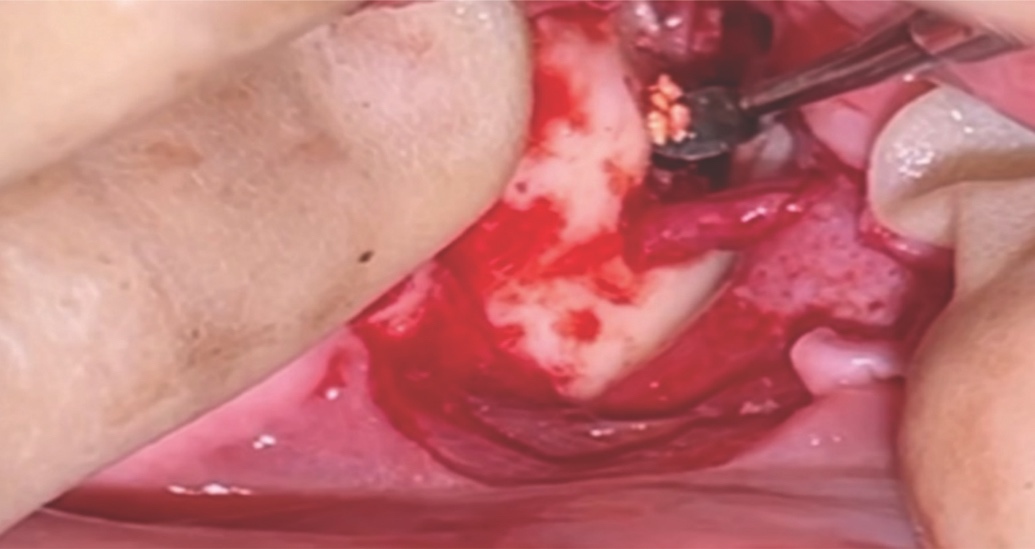

A unilateral sagittal split osteotomy was performed using piezosurgery to protect the nerve. The alveolar nerve, extending from the apical region of the left first and second molars to the mental foramen, was uncovered, and a meticulous dissection was performed to release it from the canal. Notably, rigid paste debris was observed in proximity to and within the nerve canal. The nerve exhibited signs of swelling and was surrounded by granulation tissue (Figures 4 and 5).

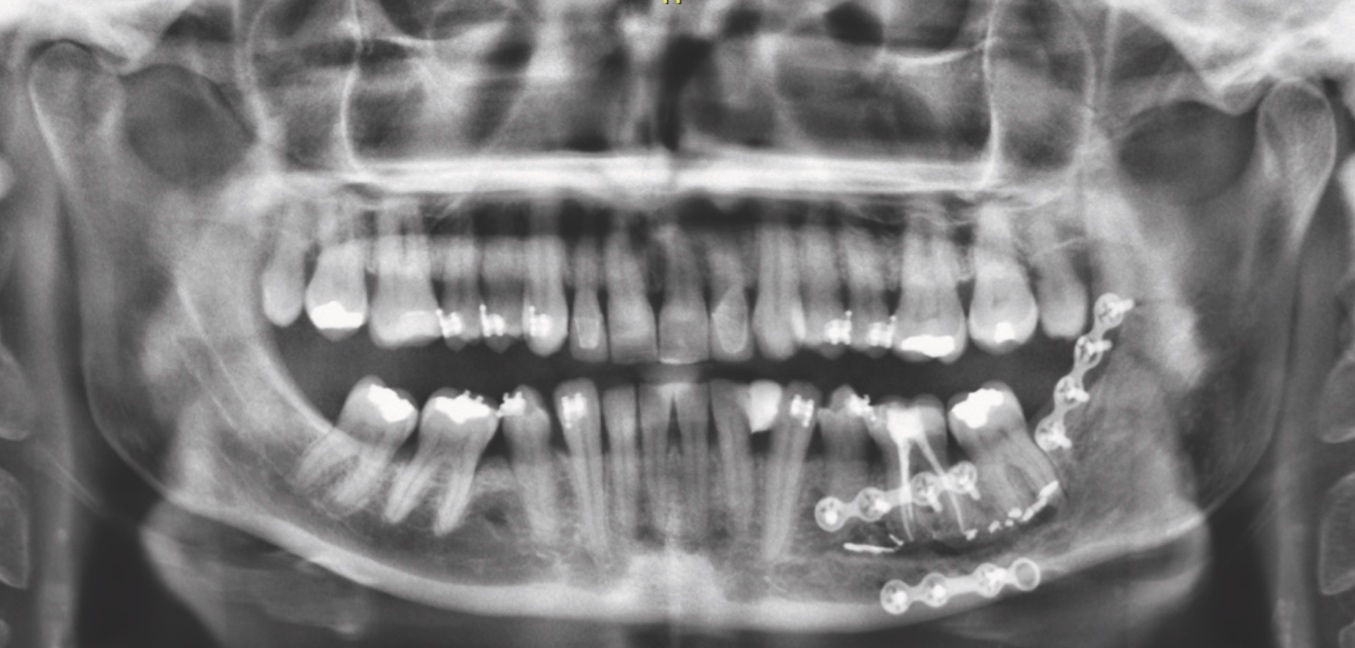

A thorough cleaning procedure ensued, followed by the repositioning of the two mandibular cortices, securing them in place with AO 5mm diameter bicortical screws, and without insertion of intermaxillary fixation (IMF) screws. Orthodontic brackets were used to stabilise the occlusion for six weeks (Figure 6).

Two weeks after the surgery, the patient reported that the pain was significantly improved, with only a tingling sensation remaining. The feeling of pressure was completely relieved. At one-year follow-up, sensation was restored and no pain was reported.

Discussion

This case report illustrates a treatment option for managing endodontic sealer extrusion following a serious endodontic complication. A 42-year-old patient underwent a unilateral sagittal split osteotomy to remove an extruded endodontic sealer from the inferior alveolar canal. Despite careful dissection and debridement of the nerve, complete removal of the sealer was not achieved, as the objective was to relieve pressure and toxicity by removing as much material as possible without causing nerve damage.

The anatomical proximity of the premolar and molar apices to the mandibular canal necessitates careful radiographic evaluation during the planning of endodontic treatment. In some cases, the apices of the molar teeth are in contact with the mandibular canal, which can cause inadvertent extrusion of the root canal sealer. An initial pretreatment radiograph of the mandibular teeth will reveal the proximity of the canal to the apices. Taking a radiograph during endodontic treatment is a necessary step in ensuring the correct working length, as well as preventing perforation and possible subsequent damage to the IAN.

Several factors could lead to sealer extrusion, including: over-instrumentation of a root canal with manual or rotary instruments; excessive pressure; and/or, poor adaptation of the gutta-percha apically, allowing sealer to be extruded through the apical foramen with warm condensation techniques.7,10,11 Additionally, the method of placing endodontic sealer has a significant impact. Studies suggest that using a Lentulo spiral exerts less intracanal pressure than the use of a syringe when applying filling pastes.12 Hence, it is imperative when injecting root canal sealer into canals that the tip does not bind in the canal and gentle force is exerted. Overextensions can be prevented by maintaining accurate working lengths and careful obturation techniques. Younger patients with wider root canal systems or cases of apical resorption may lack an adequate apical stop to prevent the extrusion of gutta-percha or endodontic sealers. In such situations, techniques that create apical barriers using calcium hydroxide or mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) may be beneficial.

The literature highlights the potential for trauma to the IAN due to overextended root-filling material in the mandibular canal, particularly given the close anatomical proximity of the mandibular canal to the apices of posterior mandibular teeth. It has been reported that IAN injuries after endodontic treatment account for 1.4-6% of total trigeminal nerve injuries.13–15 Clinical reports attribute post-endodontic paraesthesia, dysaesthesia, and pain to two fundamental mechanistic factors. The first causative mechanism of peripheral nerve injury is compression. The confined anatomical space of the osseous mandibular canal renders the enclosed nerve susceptible to compartment syndrome. Compression of the nerve’s arterial blood supply induces an acute phase characterised by heightened vascular permeability, oedema, and ischaemia, resulting in diminished oxygen delivery to the nerve.16,17 Despite the peripheral nervous system’s inherent resilience to ischaemia, prolonged exposure to stretch and compressive forces can instigate irreversible changes, including fibroblast invasion, scarring, and fibre degeneration. Recovery from nerve damage is contingent upon the duration and severity of the trauma. Thus, immediate decompression of the compartment is imperative to avert irreversible sequelae such as reactive fibrosis or neuroma.

The second causative mechanism of peripheral nerve injury is chemical neurotoxicity. Eugenol, a derivative of phenol, can infiltrate the nerve and induce protein coagulation, leading to the chemical destruction of the axon.8

In the context of surgical interventions, decortication and apicectomy are commonly employed techniques for endodontic sealer removal. However, sagittal osteotomy emerges as a highly effective method, particularly when addressing nerve compression around the second or third molars. In this specific region, characterised by thicker bone between the nerve and the periosteal surface of the buccal cortex and limited visual control, decortication or apicectomy become more challenging and less secure, heightening the risk of nerve injury. Sagittal osteotomy, routinely utilised in orthognathic surgery, facilitates a clear and extensive exposure of the nerve along a significant portion.

Conclusion

In conclusion, as the severity of nerve damage escalates with the duration of the injury, prompt surgical exploration, involving the removal of material and decompression of the IAN, is imperative and effective upon the early manifestation of sensory disturbances. Thus, emphasis should be placed on exercising caution during root canal treatment, and obtaining radiographs both during and after the procedure. Ensuring a timely referral for surgical evaluation is also critical.

Ethical statement

Written informed consent describing the purpose and scope of this study has been obtained from the patient who was included in this study.