Introduction

In Queen’s University Belfast, the primary degree in dentistry is the Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) in the Faculty of Medicine, Health, and Life Sciences. Distinctions are awarded to the top 10% of students, providing they achieve at least 70% overall and pass at first attempt. Between 2014 and 2019, a higher percentage of females typically achieved honours (8.6%) or distinctions (37.8%) when compared with males (2.2% and 26.4%, respectively). Furthermore, during the same period, an average of 24% of females were awarded medals and/or prizes compared with 12% of males.

Previous studies have looked at the differences between male and female undergraduate students’ academic performance in health-related disciplines, including nursing1 and medicine.2,3 Student ability, family motivation, the quality of secondary education, and learning styles have been suggested as possible explanations for differences in academic achievements between genders.4–6 However, there is limited research into the learning styles and preferences of dental undergraduate students.

While learning styles have been widely discussed in education, systematic reviews have found little evidence that tailoring teaching to learning style preferences improves outcomes.4,5 In fact, focusing on learning styles may not be an effective use of limited educational resources and may even limit students’ beliefs in their own learning ability.1 Nonetheless, understanding students’ preferences may offer insights into their engagement with different teaching methods.

Understanding students’ learning styles can be effective in organising and modifying the learning environment, and the teaching and learning process.6 Learning style refers to an individual’s preferences for learning, including how one absorbs, processes, and retains new information.7 There are several methods to measure learning styles, with the VARK questionnaire developed by Fleming and Mills (1992) being the most widely used. VARK is an acronym for the sensory modalities used to present information.8

Visual learners (V) process information by studying or drawing tables, diagrams or pictures. Aural learners (A) prefer to hear the information and process information best by listening to lectures, attending tutorials, and using tape recorders to play back learning sessions. They prefer to listen rather than take notes. Read-write learners (R) prefer to see the written words. They like to read text and take notes verbatim and re-read these. Kinaesthetic learners (K) prefer to acquire information through experience and practice, and prefer to learn information that has a connection to reality. They use live experience and practice to learn (Figure 1).

A learner’s style preference can be singular with one main preferred modality, bimodal with two preferences, trimodal with three, or quad-modal with the preference including all four types. Multimodal refers to a preference for more than one learning style (e.g., bimodal, trimodal or quad-modal). As a tool to evaluate learning style preferences, the VARK questionnaire has achieved widespread use among different study populations in undergraduate and postgraduate settings. This is due to its validity, relative ease of implementation, simplicity and reliability.8 For example, Childs-Kean et al. (2020) explored students’ learning styles using the VARK model in different health programmes including medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, and nursing, finding that learning styles of students varied between programmes.9

At Queen’s University Belfast, the dental curriculum incorporates a range of teaching methods, including lectures, small group tutorials, clinical practice, and laboratory sessions, which align with various VARK modalities.

Methods

The primary aim of this study was to explore the learning style preferences of clinical dental students. Secondary aims were to investigate associations between learning style and: (a) gender; and, (b) academic achievement (honours or distinctions). Following a successful application for ethical approval within the Faculty of Medicine, Health and Life Sciences, the VARK questionnaire was completed voluntarily by fourth- and fifth-year undergraduate dental students at Queen’s University Belfast. Only fourth- and fifth-year students were included as they have completed the majority of the clinical curriculum, providing a more consistent basis for comparison. The anonymised survey was distributed to a total of 120 students via email, which included a description of the study, a consent page, and a link to the questionnaire in Microsoft Forms.

The questionnaire consisted of 24 multiple-choice questions, each with four options. The students were requested to choose more than one option if applicable. Questions one to nine captured demographic information and questions 10-24 focused on VARK learning styles. The distribution of the VARK preferences was calculated according to the guidelines provided on the VARK website. Accordingly, learning preferences were categorised as unimodal (V, A, R, or K), bimodal (VA, VR, VK, AR, AK, and RK), trimodal (VAR, VAK, VRK, and ARK), or quad-modal (VARK).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise demographic data and learning style preferences. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables (e.g., learning style preference by gender, and by distinction or honours status), with significance set at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.

Results

A total of 86 respondents completed the questionnaire, 48 from BDS IV (34 female, 14 male) and 38 from BDS V (24 female, 14 male). This was a response rate of 72%. Of the respondents, 67% were female and 33% male. The gender distribution within each year group was similar to the overall cohort, with females comprising approximately two-thirds of respondents in both years.

A total of 73 students were in the 21-24 year age category, 13 were older than 25, and 20% were postgraduate students.

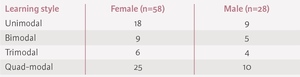

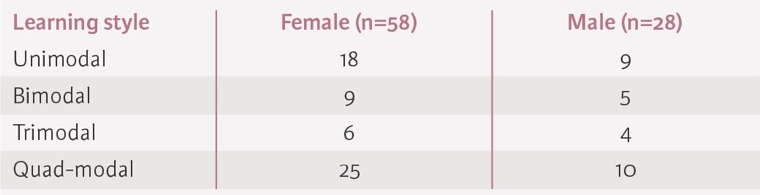

Of the study group, 69% (N = 59) preferred multimodal learning styles. The most common learning style was quad-modal (VARK) at 41%, the next most common being unimodal (31%), then bimodal (16%) and trimodal (12%). Table 1 summarises the distribution of learning style preferences by gender. There was no significant difference between males and females.

The most preferred unimodal learning style was kinaesthetic (K), with 20 of the 27 (74%) unimodal learners preferring this method. The most preferred bimodal style was visual and kinaesthetic (VK), and the most preferred trimodal style was visual, read/write and kinaesthetic (VRK).

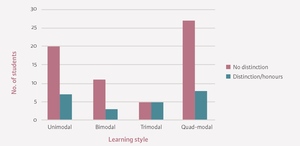

A total of 23 students had received at least one distinction or honour throughout the course of their dentistry exams, accounting for 18% of male students and 31% of females. Students self-reported if they had received an honour or distinction on the anonymised questionnaire. There was no significant difference between those with or without distinctions. No significant differences were observed in learning style preferences or distinction rates between BDS IV and BDS V students (Figure 2).

Discussion

There is a relative abundance of studies analysing different learning styles in variable fields such as medicine, engineering, nursing, and allied health specialties. However, studies examining VARK learning preferences among dental students are few, especially within the UK and Europe. The objective of this study was to investigate the learning preferences of dental students in Queens University Belfast, while examining the effects of gender, and whether attainment of distinctions/honours had any relationship with learning style preferences.

Most students in the present study preferred a multimodal learning style with no significant difference between bimodal, trimodal, and quad-modal styles. This in in agreement with the findings of previous studies from Saudi Arabia and the USA that multimodal style is the dominant learning preference among undergraduate dental students.10,11 In contrast, Nazir et al. (2018) found that 76% of dental students preferred a single learning style.12 However, this difference may be explained by research suggesting that learning preferences can change over time and between different academic environments.9

Of the students preferring a unimodal learning style, kinaesthetic (K) was the most common followed by visual (V). K has been a preferred style of dental undergraduates in several international studies, suggesting that students prefer more active learning strategies.12–14 It is likely that most undergraduate dental programmes already incorporate hands-on learning with visual components such as the use of models and explanatory videos.

The predominance of multimodal learning preferences among clinical dental students may reflect the complexity of dental education, which requires the integration of visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinaesthetic skills. Clinical dentistry involves not only theoretical knowledge but also practical skills and patient communication, necessitating a flexible approach to learning. This aligns with the demands of oral care, where students must synthesise information from multiple sources and modalities to provide comprehensive patient care.

In relation to gender preferences, there were no significant differences in learning style between female and male dental students. This is in agreement with Murphy et al. (2004), Al-Saud (2013), and Nasiri et al. (2016), where no significant differences were observed between genders among dental students.11,13,14 Conversely, Aldosari et al. (2018) found that female dental students had a significantly higher preference for bimodal learning styles when compared with their male counterparts, indicating that variability in gender preferences may exist in different contexts.10 However, this study only focused on dental students at a single institution in Riyadh, specifically including students from the third and fourth years.5

Al-Saud (2013), Aldosari et al. (2018), and Nazir et al. (2018) have all reported an association between a dental student’s GPA (Grade Point Average) and their learning style preference, and found that students with low GPA demonstrated unimodal learning style, whereas students with higher academic performance had multimodal learning style preferences. However, in this study, no significant difference was noted in learning style between those with and without distinctions/honours, suggesting that differences may be a result of other factors. Nazir et al. (2018) investigated learning styles among dental students in Saudi Arabia, including students from all years of study, which may explain the higher proportion of unimodal preferences compared to our senior-only cohort.

From the present data, it is clear that a higher percentage of females achieved distinctions or honours when compared with males, in keeping with previous years. This is in agreement with a study of 770 fourth- and fifth-year Jordanian dental students.15 Sawair et al.'s (2009) results showed that the cumulative GPAs of the female graduated students were significantly higher than those of the male students. Similarly, Nawa et al. (2020) found that males were significantly associated with lower GPA trajectories and withdrawal or repeating years among Japanese dental students.16 However, the present finding that there appears to be no significant difference between the learning styles of either female and male or those with or without distinctions, suggests that other factors, such as study habits, motivation, or external support, may contribute to the observed gender disparity in academic achievement. Further research is warranted to explore these potential influences.

No association was found between learning style and gender or distinctions/honours. This may be because none exist, or because the study was under-powered. No power calculation was used as this was a convenience sample, which may limit the ability to detect subtle associations.

While understanding learning preferences may inform curriculum design, there is limited evidence that matching teaching methods to learning styles improves outcomes.1 Overemphasis on learning styles may even restrict students’ beliefs in their learning potential.

Academic performance is likely influenced by a complex interplay of individual, environmental, social, and cultural factors. Focusing solely on gender may oversimplify the issue; future research, including qualitative studies, could provide deeper insights.

Conclusion

Differences in learning style do not appear to explain the differences in academic attainment experienced among female and male undergraduate dental students in Queen’s University Belfast. Further research will be required to explore other explanations for this, including individual, environmental, social, and cultural factors. Given the lack of evidence that adapting teaching to learning styles improves outcomes, caution is warranted in using learning style information to inform curriculum design.