Introduction

The relevance and value of behavioural sciences in dentistry has been increasingly recognised in undergraduate curricula in recent decades.1,2 The latest General Dental Council’s (GDC) Safe Practitioner framework of behaviours and outcomes for dental professional education outlines the need for graduates to be able to: “Explain and evaluate psychological and sociological concepts and theoretical frameworks of health, illness, behavioural change and disease and how these can be applied in clinical practice (C1.7)”.3 Additionally, they must be able to: “Provide patients/carers with comprehensive, personalised preventive advice, instruction and intervention in a manner which is accessible, promotes self-care and motivates patients/carers to comply with advice and take responsibility to maintain and improve oral health (C2.5.1)”.

Developing appropriate and engaging teaching methods to meet these objectives can be a challenge, especially given an educational context in which some undergraduate dental students view communication skills and patient adherence components of the behavioural sciences curriculum to be ‘more boring’ and ‘less relevant’ than their other, more clinical-based, training.4 A possible reason for this is that there is typically less teaching time dedicated to behavioural sciences topics in the dental education curriculum,5 and few dental schools have a specifically appointed lecturer with psychology expertise to deeply integrate those topics with other curricular themes in dedicated modules.

While some dental schools may teach dental undergraduates individual evidence-based behavioural approaches to disease prevention, such as the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE) Making Every Contact Count Programme, few actively train students in specific behavioural interventions. Discussions centred on behavioural modification represent one preventive strategy employed by dental care practitioners to encourage patients to adopt healthier habits and routines. Motivational interviewing (MI) is a behaviour change conversation technique that involves assessing individuals’ readiness to change, enhancing their self-efficacy, and facilitating adherence to healthcare recommendations.6 Dentists generally do not have MI as part of their compulsory training, but may learn this skill as part of continuing personal development. Recent research has highlighted the potential benefits of behaviour change conversations in promoting better oral health, suggesting that they can be effective in managing dental diseases,7 enhancing patient motivation to adopt healthier oral hygiene behaviours,8 and building clinicians’ communication strategies to improve patient engagement.9

Despite the benefits of behaviour change conversations in the promotion of better oral health, focus groups involving various members of the dental team in England (dentists, practice managers, dental therapists/hygienists, dental nurses) report numerous challenges to supporting dental patients’ behaviour change.10 In particular, many struggle with conversational elements, including building rapport and expressing empathy with parents of children with tooth decay. Instead, they report mostly relying on an information-giving approach, contrary to growing evidence that motivational approaches to behaviour change (i.e., eliciting change) can be especially effective at preventing oral disease in children.11

Training dental students in the application of behaviour change skills provides a strong educational tool based on psycho-educational theories.12 Theory-informed training can effectively increase dental care professionals’ motivation to discuss behaviour change with patients.13 Although numerous studies have assessed the impact of general communication training on dental undergraduates’ ability to interact with patients effectively,14–16 to the best of our knowledge, no studies to date have evaluated the training of dental students in a specific behaviour change conversation intervention.

The Dental RECUR Brief Negotiated Interview (DR-BNI) is a behavioural intervention for caries prevention, with strong evidence of its effectiveness (29%) in the reduction of new dental caries in children aged seven to nine years.11 The approach involves dental nurses applying motivational interviewing skills and behaviour change techniques in a 30-minute behaviour change conversation to motivate parents of children with caries to develop one or two personalised goals based on national preventive recommendations.17

The DR-BNI draws upon frameworks of behaviour change science, clinical communication skills, and disease prevention. As such, it has strong potential as an educational model for dental undergraduates to develop knowledge and competency in engaging a dental patient in a behaviour change conversation. DR-BNI-related communication skills could be implemented by dental students during both simulated and real interactions with dental patients throughout their training and in future practice. There is flexibility in how, and to whom, the DR-BNI is taught; a DR-BNI hands-on workshop has been successfully delivered to behavioural scientists, academics, and professionals.18 Typically, DR-BNI training involves teaching participants about the problem of child dental caries, motivational interviewing, behaviour change science, and information on how to deliver the DR-BNI in clinical practice. This is followed by supervised role-play, during which participants practice DR-BNI skills and receive feedback from a DR-BNI trainer. All components of the DR-BNI training could be readily adapted for delivery to dental undergraduates, as students are regularly taught information and skills that they then implement in practice under the supervision of an academic or clinician.

Brief hands-on workshops delivered to a small number of participants can be effective as a teaching and learning methodology for communication skills training,19 knowledge and confidence development,20 and as a means of identifying challenges for informing future practice.21 As the DR-BNI training has not previously been delivered to dental undergraduates, a brief hands-on workshop format would help to identify the potential benefits and challenges of adapting it for this demographic before it can be evaluated more widely within the undergraduate behavioural sciences curriculum.

Therefore, this study aimed to develop dental undergraduates’ behaviour change conversation skills in a training workshop on the DR-BNI.

Method and materials

The study was reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Medicine, Health and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee (Faculty REC) in accordance with the Proportionate Review process at Queen’s University Belfast (Faculty REC Reference Number: MHLS 24_121).

Participants

Undergraduate dental students across years one to five were invited to take part in an in-person behaviour change conversation skills workshop via an invitation email. Participants were 17 dental undergraduates enrolled in the five-year Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) programme at Queen’s University Belfast during the 2023-2024 academic year who had registered to participate in the DR-BNI workshop via an online form. Participants were between 19 and 26 years of age, and none had completed a previous degree. Participants were comprised of students from year one (52.9%), year two (5.9%), year four (35.3%) and year five (5.9%) of their studies. There were a range of ethnicities, with most identifying as ‘White British’ (17.6%), ‘Irish’ (17.6%), ‘Any other ethnic group’ (17.6%), or ‘Pakistani’ (11.8%). Participants were compensated with a £10 Amazon voucher and provided with a completion certificate following attendance at the workshop.

Participants’ identifiable information, including email addresses, were kept confidential and stored in a password-encrypted university database. When participants completed the consent form, they were asked to create a non-identifiable unique ID code, which they used when completing all questionnaires.

Procedure

Pre-evaluation

Participants who consented to participate in the evaluation of the DR-BNI training workshop were sent a ‘pre-evaluation questionnaire’ via Microsoft Forms in advance to be completed and returned to the Chief Investigator before the workshop. This questionnaire collected participants’ demographic information, their current knowledge of DR-BNI-related topics such as oral health behaviour change and motivational interviewing, and how confident they are in applying relevant skills to clinical practice. This questionnaire also collected qualitative data relating to participants’ expectations for the training.

Workshop

During the 90-minute workshop, a behavioural scientist trained in the DR-BNI intervention (the Chief Investigator, ME) delivered a brief talk on how it was developed and evaluated. This was followed by hands-on training including supervised role-play facilitated by the Chief Investigator (ME) and the Co-Investigator (MH).

The role-play involved participants working in pairs, with one participant role-playing as a dental student delivering the DR-BNI, and the second participant role-playing as a parental caregiver receiving the DR-BNI. Finally, there was a whole-group discussion during which participants shared whether the training met their expectations and if they felt they had successfully met the learning objectives.

Post evaluation

A 13-item post-evaluation questionnaire was developed using the four-level Kirkpatrick Model22,23 to assess: how engaging and relevant participants found the training (Level 1: Reaction); the extent to which they acquired the intended knowledge, skills, and confidence (Level 2: Learning); the extent to which they were able to apply what they learned (Level 3: Behaviour); and, whether training contributed to the learning objectives of the dental undergraduate curriculum (Level 4: Results). This questionnaire was completed by participants one week following the workshop to allow time for participants to practice using MI communication skills with either a dental patient or friend/family member.

Results

Post-training evaluation

Participants indicated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) the extent to which they agreed with the statements, with participants either somewhat or strongly agreeing with all post-training evaluation questionnaire items (M = 4.31, M = 5.00) across all four domains of Kirkpatrick’s Model (Table 1).

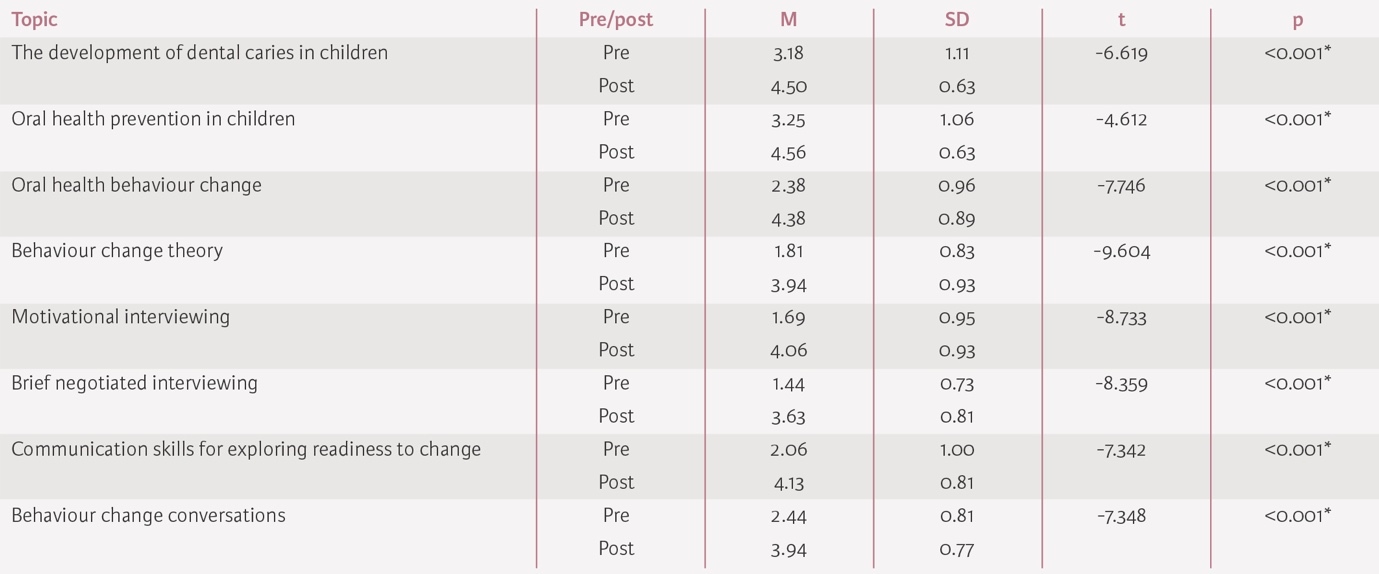

Pre-post evaluation: knowledge

Participants reported their knowledge of DR-BNI-related topics on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all knowledgeable, 5 = extremely knowledgeable), with a paired-samples t-test finding that participants’ knowledge of all DR-BNI-related topics and skills had significantly increased following the training (Table 2).

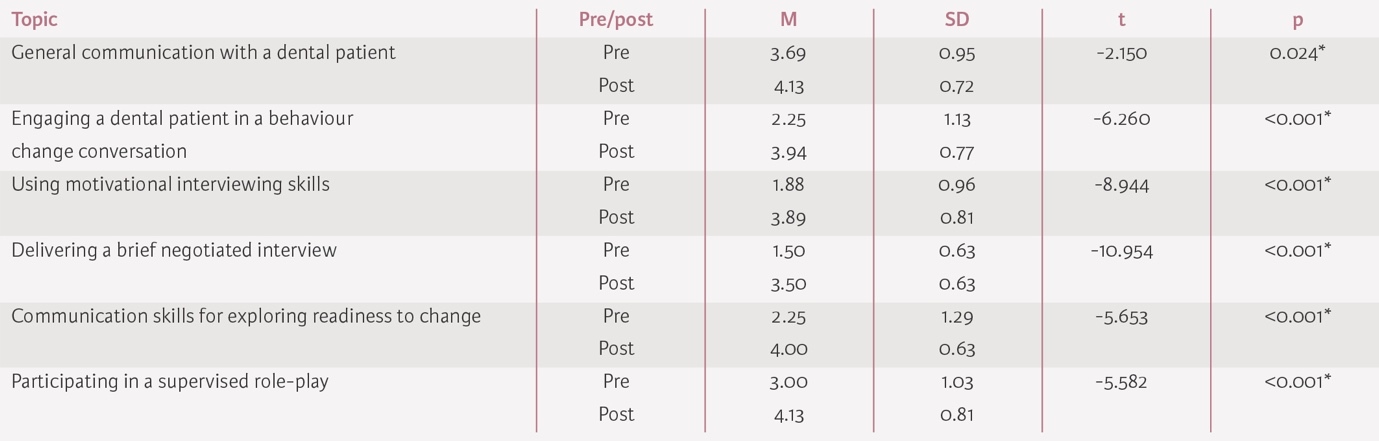

Pre-post evaluation: confidence

Participants reported their confidence in applying DR-BNI-related skills to clinical practice on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all confident, 5 = extremely confident), with a paired-sample t-test finding that participants’ confidence had significantly increased following the training (Table 3).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a DR-BNI workshop on dental undergraduates’ behaviour change conversation knowledge and confidence, and to identify the benefits and challenges to embedding training in this approach within the undergraduate behavioural sciences curriculum. The findings of this study demonstrate the potential of DR-BNI training to enhance dental undergraduates’ knowledge of, and confidence in, delivering a behaviour change conversation with a dental patient.

The results of this study may benefit both dental educators and students. The learning objectives of DR-BNI training align closely with those of the GDC’s safe practitioner framework, meaning that this may be an effective educational tool for developing students’ communication skills for delivering personalised preventive advice, and their knowledge and application of theoretical frameworks of health, illness, behavioural change and disease. Previous research in this area has recommended better equipping dental students with the necessary tools to adopt a more holistic and person-centred approach to improving patient health outcomes.24 Incorporating DR-BNI training more comprehensively within the dental curriculum has the potential to effectively address the existing gaps in students’ exposure to behavioural sciences and, more specifically, oral health behaviour change conversations.

The potential benefits of DR-BNI training extend beyond the immediate educational context to broader public health outcomes. Equipping future dental practitioners with communication skills to effectively engage patients in an oral health behaviour change conversation could result in reduced disease prevalence. Increasingly, non-judgemental and empathetic communication skills are considered effective at fostering a deeper understanding of patients’ psychological and social contexts, ultimately promoting more equitable and patient-centred care to prevent disease progression.25

Limitations and future directions

The DR-BNI training was delivered as a standalone workshop rather than embedded within the broader behavioural science curriculum. Achieving competence in communication and interpersonal skills requires the iterative process of experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting.8 However, this may not have been possible in the week between the workshop and the post-evaluation questionnaire in the present study. The condensed format of a workshop may have limited the depth of training, leaving gaps in areas such as motivational interviewing and the full application of behaviour change science to the management of children’s oral health. Delivering the training as part of a combined lecture and workshop series in a behavioural science module across an academic term with formative and summative assessment of skills would allow for iterative learning and practice.

Participants were mostly comprised of students from the first two years of their training. While these students have fewer ‘real’ clinical/patient interactions than year three-five students, patient-facing communication skills and behavioural sciences are taught during these years and they frequently have opportunities to practice communication skills in simulated scenarios, so did have some knowledge and experience in advance of participation (albeit to a lesser extent than their senior colleagues).

Future studies may wish to examine the practical application of DR-BNI-related skills in real versus simulated dental patient interactions. The use of fidelity monitoring checklists or structured proformas could provide deeper insights into how effectively students apply these skills in practice. Additionally, exploring the long-term impact of such training on patient outcomes and health behaviours would further validate the public health significance of incorporating the DR-BNI approach.

Despite dental caries being the most preventable childhood disease, there remains a significant health burden on individuals, their families, and the National Health Service (NHS), with 25% of five-year-old children affected.17 It is vital that dental students are trained in, and are confident delivering, a range of approaches to prevent and treat this disease by the time they begin practising, whether as a ‘safe beginner’ (as per the GDC), or as an independent provider (as per the Dental Council of Ireland).

Conclusion

Training dental undergraduates in effective evidence-based approaches to prevention has the potential to benefit both students in the present and patients in the future. Behaviour change conversations are ideal for teaching students about psychological frameworks of health, illness, and disease, and how to provide personalised preventive advice in clinical practice. The DR-BNI intervention has potential as an educational model for developing dental undergraduates’ behaviour change conversation skills; future research should investigate the utility of its inclusion within the dental undergraduate curriculum.