Introduction

Mandibular third molars are innervated by the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN), part of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve, which arises deep to the lateral pterygoid muscle and passes through the inferior alveolar foramen to enter the mandible. The IAN is a mixed nerve with its sensory component supplying sensation to the mandibular teeth, lower lip and chin.1

Paraesthesia is a transient or chronic sensory abnormality of the nervous system, which can manifest as a tingling, sharp or numb sensation. Systemic causes of paraesthesia include connective tissue diseases, diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders and metastatic disease, whereas local factors include mechanical, thermal and toxic insults.2 IAN paraesthesia is a known risk of mandibular third molar surgery, occurring temporarily in up to 2% of patients and permanently in 0.5% of patients.3 Coronectomy is an effective management option to reduce the risk of nerve injury when managing mandibular third molars closely associated with the IAN canal. Careful case selection is crucial, as there are several contraindications relating to both tooth and patient. The guideline relating to the management of mandibular third molars by the Royal College of Surgeons, England, contraindicates coronectomy for third molars with caries into the pulp, apical disease or mobility. Patient contraindications include those who are immunocompromised or at increased risk of osteoradionecrosis.4 Horizontal impaction is also considered a relative contraindication for coronectomy due to the potential risk of inadvertent damage to the IAN when cutting inferiorly for decoronation.5 Renton et al. further caution against coronectomy in third molars with conical roots due to the increased risk of root mobilisation and failure.6

Case history

A 23-year-old female patient was referred to the oral medicine department by her general dental practitioner querying atypical facial pain, with a two-month history of intermittent numbness of the lower left lip and chin region, with occasional pins and needles sensation. Medically, the patient had well-controlled asthma and no known drug allergies. She reported multiple episodes of numbness affecting the left side of her lower lip and chin occurring daily for approximately 20 minutes with complete resolution afterwards. The patient had a normal gross cranial nerve examination with no sensory deficit noted on testing on the day of examination. The area of paraesthesia was described by the patient as confined to the left aspect of the lower lip and chin, never crossing the midline and extending to the lower border of the mandible.

Blood investigations were completed to evaluate potential deficiencies as a cause for the patient’s symptoms, including a full blood count, iron, folate, B12, and thyroid function tests. Systemic causes of neuropathy, including diabetes and connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma and Sjögren’s syndrome, were evaluated with a blood glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin and connective tissue screen. All results were within normal ranges encouraging further exploration of local causative factors.

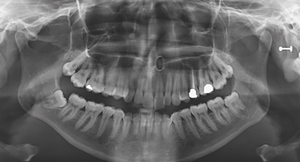

A partially erupted lower left third molar with a prominent operculum was noted during the intraoral examination. The orthopantomogram taken suggested a close relationship of the tooth with the IAN due to a relative rarefaction associated with the distal root indicating proximity of the nerve canal with little or no bone interposition (Figure 1).

Caries was also noted occlusally on the lower left second molar and a deep restoration on the upper left first molar. Following the exclusion of a systemic cause by the oral physicians, a referral was made to oral surgery to assess the possible correlation of these clinical and radiographic findings with the presenting complaint.

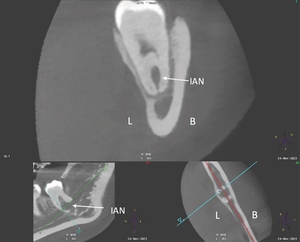

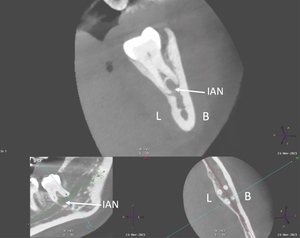

At the oral surgery consultation, the patient also noted a four-week history of intermittent discomfort in the LL8 region described as throbbing pain with associated swelling of the gum made worse by chewing and applying pressure to the tooth. This presentation was in keeping with recurrent pericoronitis. A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan was undertaken, which identified four roots of LL8 and associated loss of IAN canal cortication. The IAN pathway grooved the distobuccal root and passed between/penetrated the mesial roots (Figures 2 and 3).

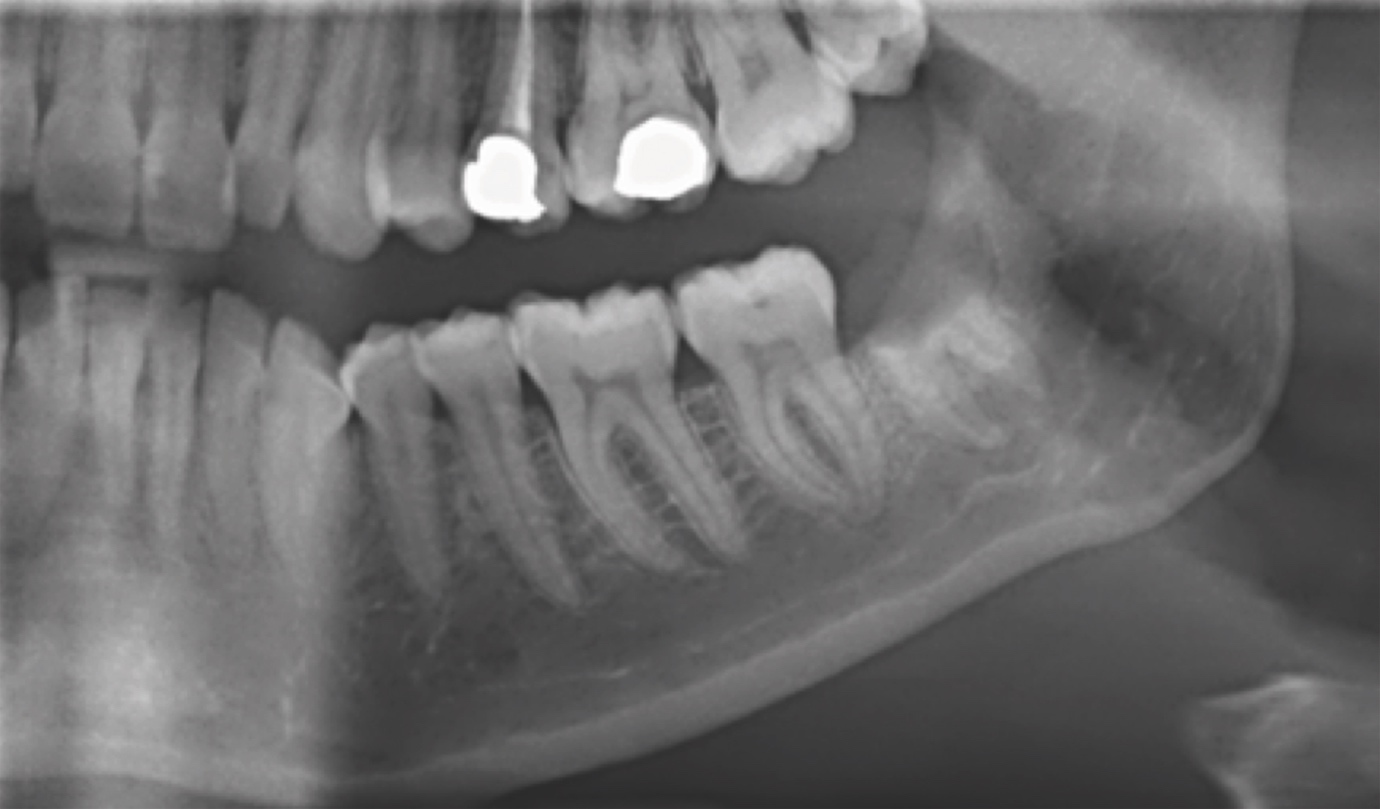

Given the temporal association between the history of paraesthesia, episodes of pericoronitis and the clinical findings, it was agreed that there was a likely causative association between the pericoronitis and the intimate relationship of LL8 with the IAN. Complete removal of the LL8 was deemed high risk for iatrogenic IAN damage. To reduce this risk, the patient was consented for a coronectomy. The coronectomy was undertaken with a short general anaesthetic without complication, and at the two-month postoperative review, the patient had complete resolution of symptoms and no postoperative sensory deficit. The orthopantomogram taken at this review shows no evidence of periapical infection and the distal retained root is satisfactorily subcrestal (Figure 4). It is acknowledged that following the coronectomy, the mesial root is not at the optimum subcrestal level and has a small radiodense area, which may be residual enamel. This necessitates close follow-up.

Discussion

This case report describes a rare example of IAN sensory disturbance that was temporally associated with and likely caused by recurrent episodes of pericoronitis around a partially erupted lower wisdom tooth. When considering differentials for paraesthesia, one should consider potential systemic and local causes. Paraesthesia of the lip and chin has been associated with the term ‘numb chin syndrome’, for which there are several underlying pathologies suggested, including neuropathies related to diabetes and multiple sclerosis, intracranial lesions, and benign and malignant tumours.7

Cranial nerve neuropathies occur more frequently in patients with diabetes compared with the general population.8 This patient reported no symptoms suggestive of diabetes, which was further excluded by a normal blood glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin level. Connective tissue diseases including scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome can also be associated with trigeminal sensory neuropathy manifesting as numbness or pain.9 Multiple sclerosis is a chronic inflammatory neurodegenerative disease, which can have orofacial manifestations, one of the most common being trigeminal sensory neuropathy.10 The patient exhibited no features of systemic disease, and all bloodwork investigations were normal.

In the absence of an odontogenic cause of IAN paraesthesia, clinicians should strongly consider exploring if the symptom could be a neurological manifestation of malignancy. Primary and metastatic lesions local to the nerve can cause paraesthesia due to perineural spread or compression of nerve tissue.11 Trigeminal nerve paraesthesia has been found in patients diagnosed with peripheral nerve sheath neoplasia, osteosarcoma of the mandible, multiple myeloma, and schwannoma lesions.12 Numbness of the chin has also been identified as a sign of relapse and progression of metastatic disease in breast cancer and lymphoma patients.13

Paraesthesia of the IAN has been noted in the literature in instances of periapical lesions affecting mandibular teeth. A case series by Devine et al.14 discusses 22 cases of patients experiencing numbness, pain and/or paraesthesia of the lip and chin resulting from periapical lesions in premolars and molars. Complete resolution of symptoms was achieved in those patients treated with extraction or root canal treatment of the affected teeth. These findings have also been reflected in a recent case report by Censi et al., which discusses two instances of infection-induced IAN paraesthesia manifesting as numbness of the chin and lip.15 In both patients, there was radiographic evidence of periapical pathology near the mental foramen and patient symptoms resolved following root canal therapy or extraction.

In the current case, there was no radiographic evidence of periapical infection. The intermittent numbness described by the patient preceded the pericoronitis symptoms by a few months; however, the enlarged operculum and impacted mandibular third molar were noted at the initial consultation. The conclusion is drawn from the temporal association with the pericoronitis events and the relationship of the IAN with the tooth, that inflammation around the crown of the partially erupted LL8 and surrounding periodontal tissues led to pressure effects with episodic compression/tension. This compression may have resulted in distortion of the IAN canal with subsequent paraesthesia. A similar case of transient paraesthesia of the lower lip and chin associated with chronic pericoronitis has been previously highlighted in a case report by Di Lauro et al.16 involving a mandibular third molar in a contiguous relationship to the IAN canal. A coronectomy was completed, resulting in a significant reduction of paraesthesia.

IAN injury is avoidable and the risk can be mitigated with thorough case history, clinical examination and radiographic assessment, with consequent appropriate treatment planning. Failure to adequately assess mandibular third molars and their proximity to the IAN can cause postoperative trigeminal sensory neuropathy resulting in long-term chronic pain and disability for up to 70% of patients.17 On radiographic plain films, diversion of the canal, darkening of the root where crossed by the canal, narrowing of the canal and interruption of the canal walls are noted to significantly increase the risk of damage during third molar surgery.18 Consequent further characterisation of canal integrity by CBCT is highly sensitive for predicting intraoperative IAN exposure and the associated increased risk of postoperative IAN paraesthesia.19 However, CBCT should not be the first-line imaging modality of choice, but rather applied in instances where suspicions are raised on 2D imaging.4 Alternative treatment options should then be explored in cases demonstrating these radiographic features.

The deliberate retention of pathology-free mandibular third molar roots through coronectomy reduces the risk of IAN injury with no adverse impact on the incidence of dry socket or periapical infection of the retained roots.6 It is possible with time that retained roots can migrate away from the IAN allowing for their extraction under local anaesthetic if indicated, with lower risk of nerve injury. In this particular case, migration of the retained roots may result in future paraesthesia if the intimately involved IAN moves with them. This finding was reported by Renton and Drage (2002), where a patient experienced a return of paraesthesia eight years post coronectomy of a right mandibular third molar perforated by the IAN.20 Radiographic investigation revealed unusual superior migration of the IAN canal as well as the retained roots. Longer-term follow-up is planned to thoroughly evaluate this case.

Conclusion

This case report highlights an unusual presentation of intermittent IAN paraesthesia associated temporally with pericoronitis of a partially erupted mandibular third molar where the IAN perforates one root and is in close proximity to the other. Treatment planning was guided by evidence-based CBCT characterisation to reduce the risk of iatrogenic IAN injury, resulting in resolution of the patient’s symptoms to date, with no postoperative sensory deficit.